Chapters

- 1. The opportunity for using open source information and user-generated content in investigative work

- Foreword

- Investigating Disinformation and Media Manipulation

- Introduction

- For the Great Unnamed

- 2. Using online research methods to investigate the Who, Where and When of a person

- Contributor List

- 3. Online research tools and investigation techniques

- What This Book Is (And What It Isn’t)

- 4. Corporate Veils, Unveiled: Using databases, domain records and other publicly available material to investigate companies

- 1. When Emergency News Breaks

- 5. Investigating with databases: Verifying data quality

- 1.1. Separating Rumor From Fact in a Nigerian Conflict Zone

- From Coffee to Colonialism: Data Investigations into How the Poor Feed the Rich

- The Handbook At A Glance

- 6. Building expertise through UGC verification

- The Age of Information Disorder

- Repurposing Census Data to Measure Segregation in the United States

- 7. Using UGC in human rights and war crimes investigations

- 2. Verification Fundamentals: Rules to Live By

- What Is Data Journalism?

- 8. Applying ethical principles to digital age investigation

- 2.1. Using Social Media as a Police Scanner

- The Lifecycle of Media Manipulation

- Multiplying Memories While Discovering Trees in Bogotá

- Why Journalists Should Use Data

- 9. Presenting UGC in investigative reporting

- Behind the Numbers: Home Demolitions in Occupied East Jerusalem

- Why Is Data Journalism Important?

- Mapping Crash Incidents to Advocate for Road Safety in the Philippines

- 10. Organizing the newsroom for better and accurate investigative reporting

- Tracking Worker Deaths in Turkey

- Some Favorite Examples

- Case Study 1. Combing through 324,000 frames of cellphone video to help prove the innocence of an activist in Rio

- 3. Verifying User-Generated Content

- 1. Investigating Social Media Accounts

- Data Journalism in Perspective

- Case Study 2. Tracking back the origin of a critical piece of evidence from the #OttawaShooting

- 3.1. Monitoring and Verifying During the Ukrainian Parliamentary Election

- Building Your Own Data Set: Documenting Knife Crime in the United Kingdom

- The ABC’s Data Journalism Play

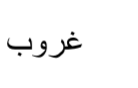

- Case Study 3. Navigating multiple languages (and spellings) to search for companies in the Middle East

- Narrating a Number and Staying with the Trouble of Value

- Data Journalism at the BBC

- 4. Verifying Images

- Indigenous Data Sovereignty: Implications for Data Journalism

- How the News Apps Team at Chicago Tribune Works

- 4.1. Verifying a Bizarre Beach Ball During a Storm

- 1a. Case Study: How investigating a set of Facebook accounts revealed a coordinated effort to spread propaganda in the Philippines

- Behind the Scenes at the Guardian Datablog

- 4.2. Verifying Two Suspicious “Street Sharks” During Hurricane Sandy

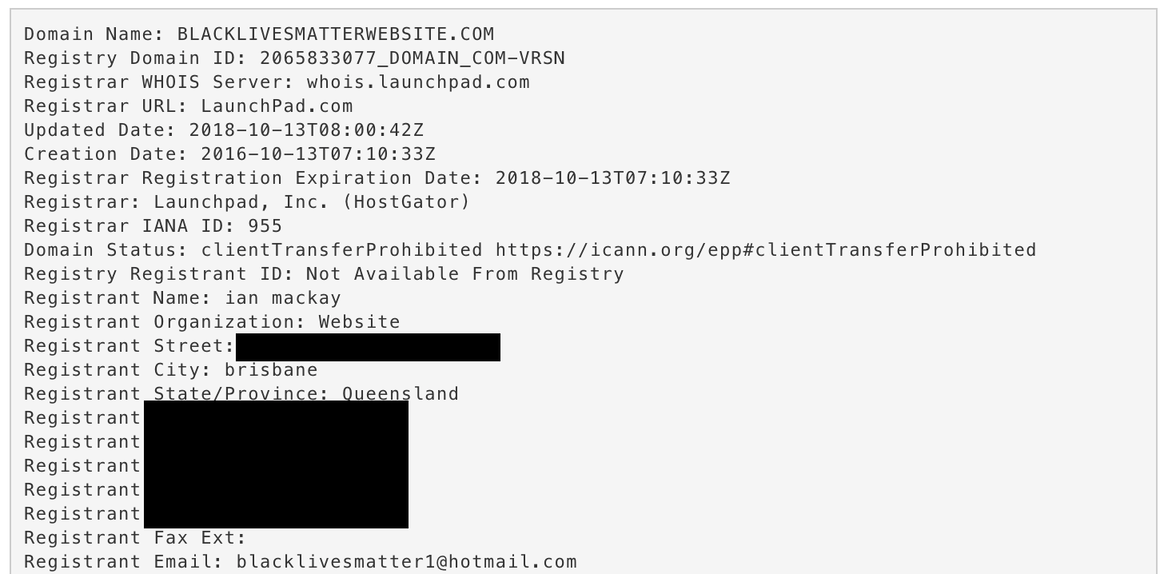

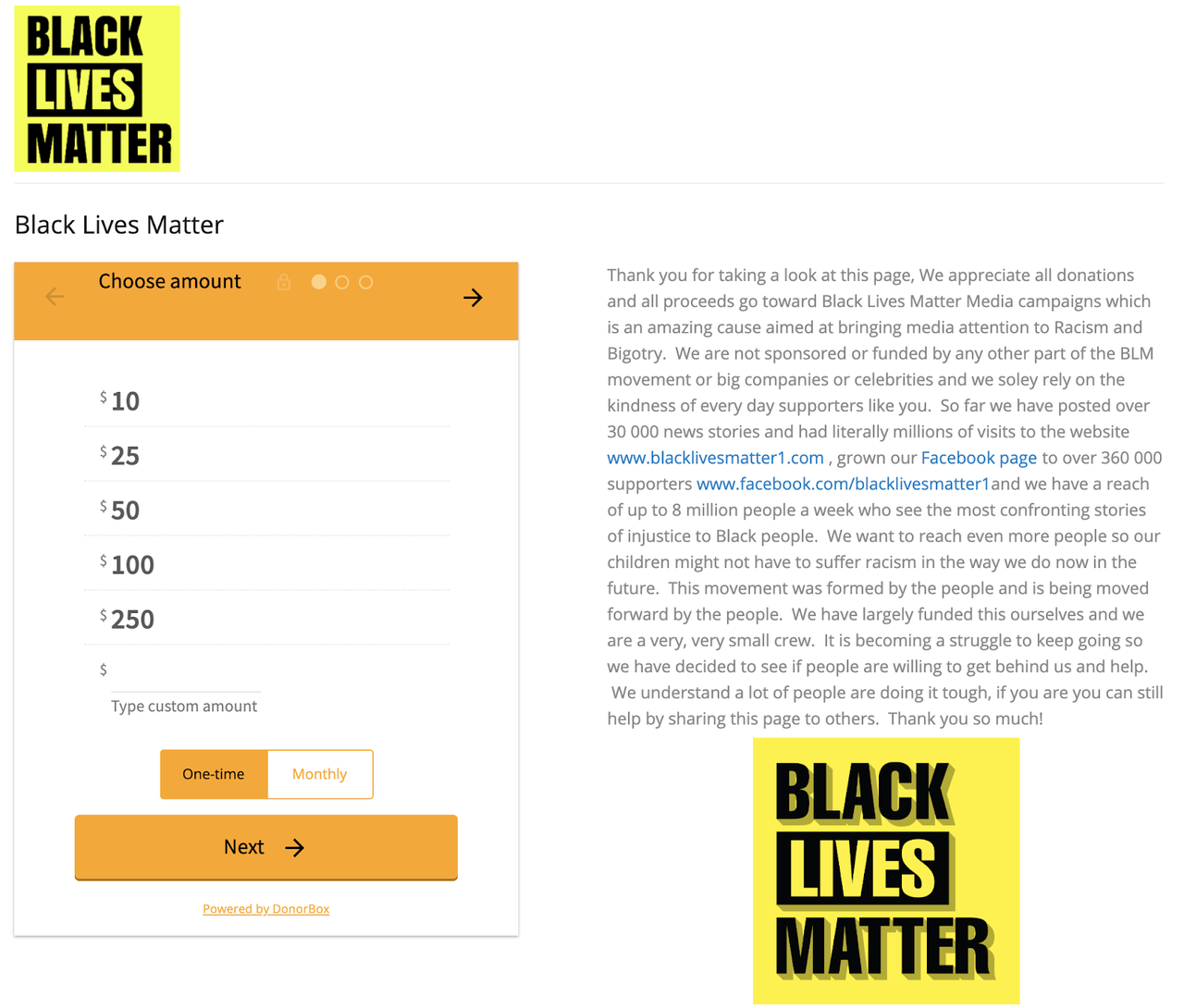

- 1b. Case Study: How we proved that the biggest Black Lives Matter page on Facebook was fake

- Alternative Data Practices in China

- Data Journalism at the Zeit Online

- 2. Finding patient zero

- Making a Database to Document Land Conflicts Across India

- 5. Verifying Video

- Reassembling Public Data in Cuba: Collaborations When Information Is Missing, Outdated or Scarce

- How to Hire a Hacker

- 5.1. Verifying a Key Boston Bombing Video

- 3. Spotting bots, cyborgs and inauthentic activity

- Making Data with Readers at La Nación

- Harnessing External Expertise Through Hackthons

- 5.2. Investigating a Reported ‘Massacre’ in Ivory Coast

- Running Surveys for Investigations

- 5.3. Confirming the Location and Content of a Video

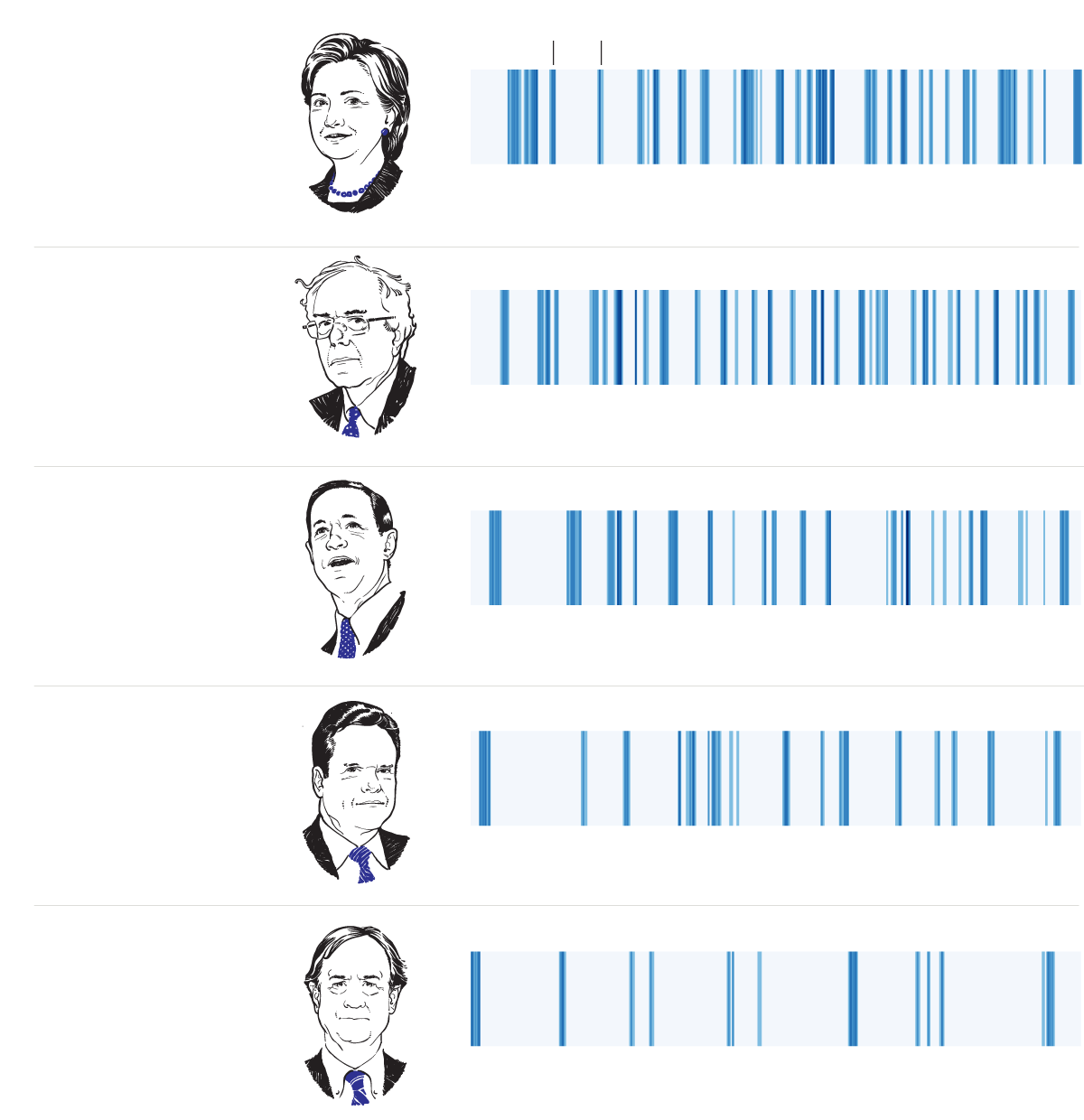

- 3a. Case study: Finding evidence of automated Twitter activity during the Hong Kong protests

- Following the Money: Cross-Border Collaboration

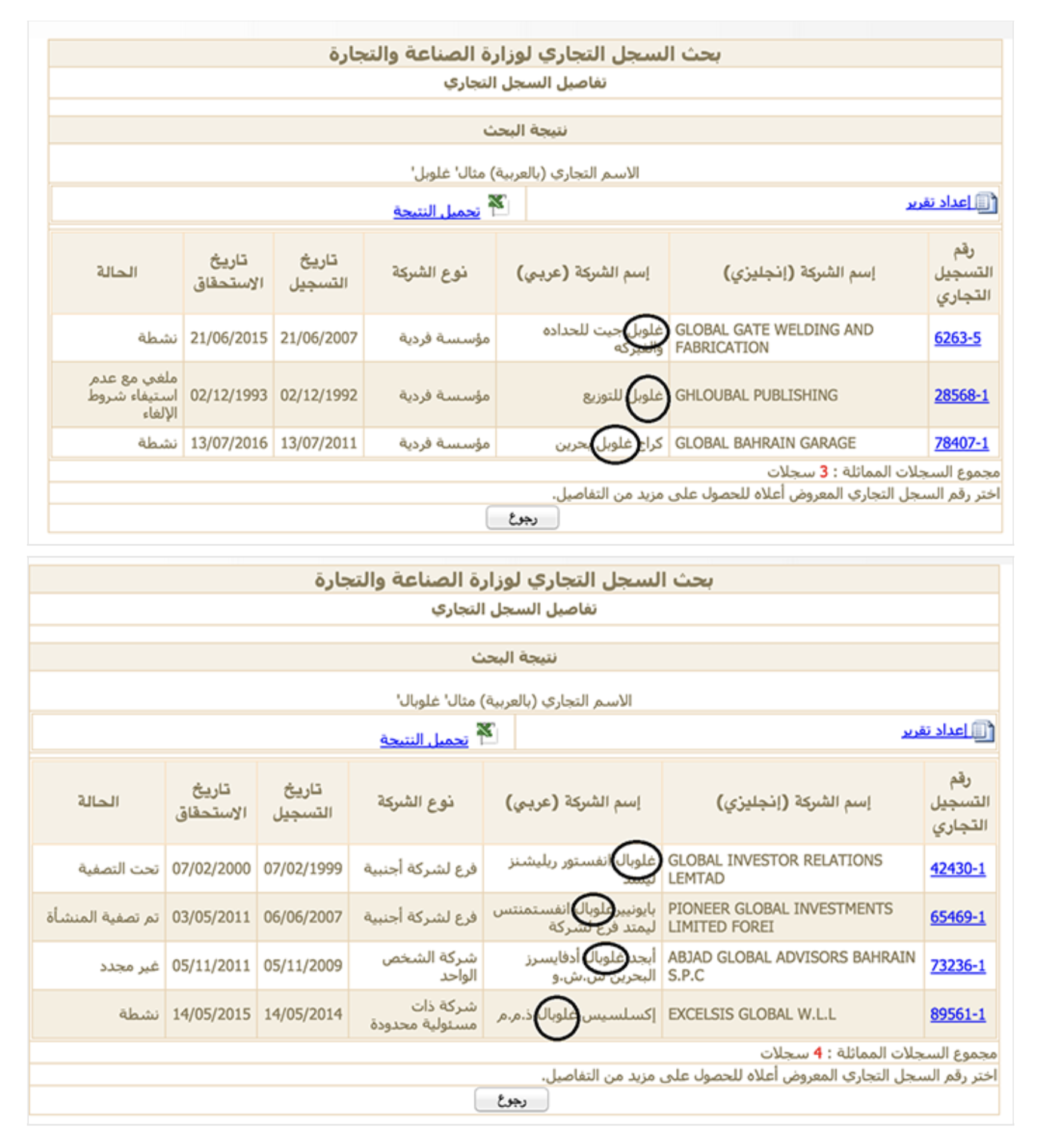

- 4. Monitoring for fakes and information operations during breaking news

- Data Journalism: What’s Feminism Got to Do With I.T.?

- Our Stories Come As Code

- 6. Putting the Human Crowd to Work

- 5. Verifying and questioning images

- Infrastructuring Collaborations Around the Panama and Paradise Papers

- 6.1. Tripped Up by Arabic Grammar

- Text as Data: Finding Stories in Text Collections

- Business Models for Data Journalism

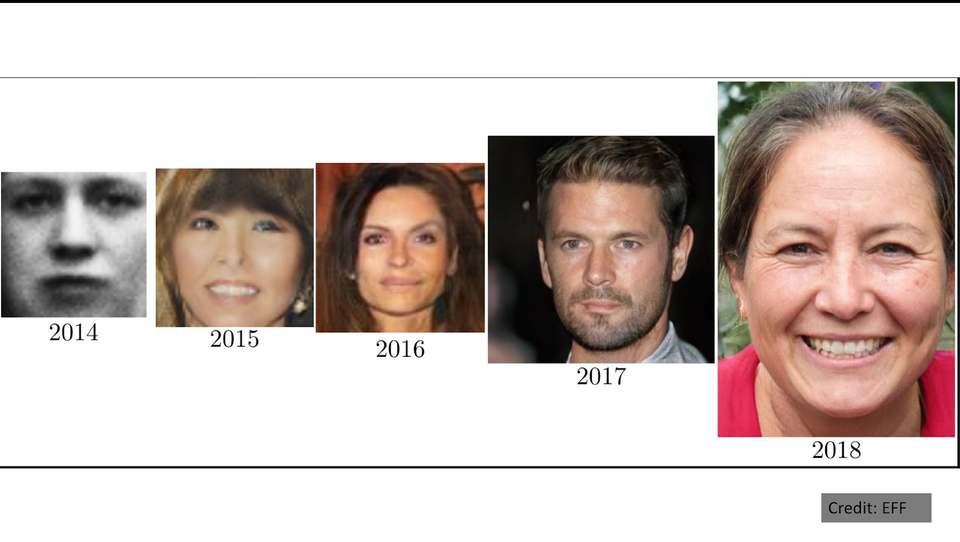

- 6. How to think about deepfakes and emerging manipulation technologies

- Coding With Data in the Newsroom

- Accounting for Methods in Data Journalism: Spreadsheets, Scripts and Programming Notebooks

- Kaas & Mulvad: Semi-finished Content for Stakeholder Groups

- 7. Adding the Computer Crowd to the Human Crowd

- 7. Monitoring and Reporting Inside Closed Groups and Messaging Apps

- 7.1. How OpenStreetMap Used Humans and Ma- chines to Map Affected Areas After Typhoon Haiyan

- 7a. Case Study: Bolsonaro at the Hospital

- Working Openly in Data Journalism

- 8. Investigating websites

- Making Algorithms Work for Reporting

- 9. Analyzing ads on social networks

- Journalism With Machines? From Computational Thinking to Distributed Cognition

- The Opportunity Gap

- 8. Preparing for Disaster Coverage

- 10. Tracking actors across platforms

- A 9 Month Investigation into European Structural Funds

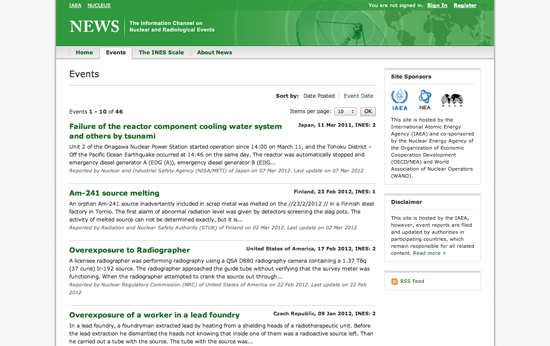

- 8.1. How NHK News Covered, and Learned From, the 2011 Japan Earthquake

- Ways of Doing Data Journalism

- The Eurozone Meltdown

- Data Visualisations: Newsroom Trends and Everyday Engagements

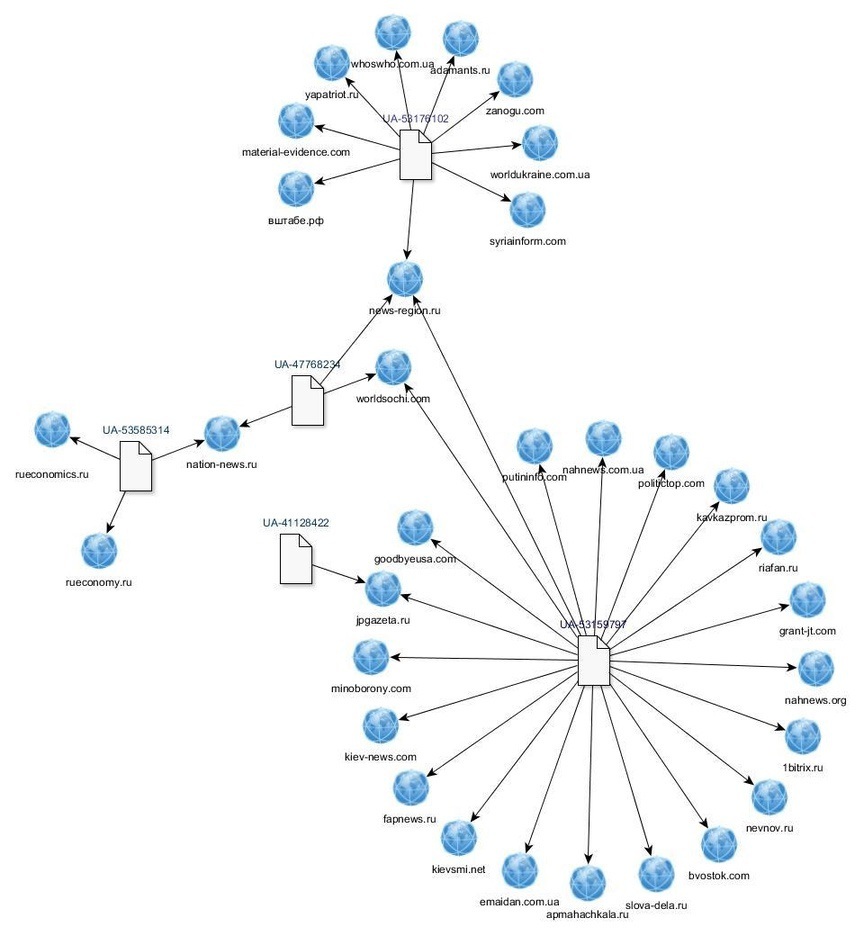

- 11. Network analysis and attribution

- Covering the Public Purse with OpenSpending.org

- Sketching With Data

- 9. Creating a Verification Process and Checklist(s)

- Finnish Parliamentary Elections and Campaign Funding

- 9.1. Assessing and Minimizing Risks When Using UGC

- The Web as Medium for Data Visualization

- 11a. Case study: Attributing Endless Mayfly

- Electoral Hack in Realtime

- 9.2. Tips for Coping With Traumatic Imagery

- Four Recent Developments in News Graphics

- 11b. Case Study: Investigating an Information Operation in West Papua

- Data in the News: Wikileaks

- Searchable Databases as a Journalistic Product

- Mapa76 Hackathon

- 10. Verification Tools

- The Guardian Datablog’s Coverage of the UK Riots

- Credits

- Illinois School Report Cards

- “VISUALIZE JUSTICE: A Field Guide to Enhanc- ing the Evidentiary Value of Video for Human Rights”

- Hospital Billing

- Care Home Crisis

- Verification and Fact Checking

- The Tell-All Telephone

- Narrating Water Conflict With Data and Interactive Comics

- Data Journalism Should Focus on People and Stories

- Creating a Verification Workflow

- Which Car Model? MOT Failure Rates

- Bus Subsidies in Argentina

- Tracking Back a Text Message: Collaborative Verification with Checkdesk

- The Algorithms Beat: Angles and Methods for Investigation

- Citizen Data Reporters

- The Fake Football Reporter

- The Big Board for Election Results

- The Story of Jasmine Tridevil: Getting around Roadblocks to Verification

- Telling Stories with the Social Web

- Crowdsourcing the Price of Water

- Stolen Batmobile: How to Evaluate the Veracity of a Rumor

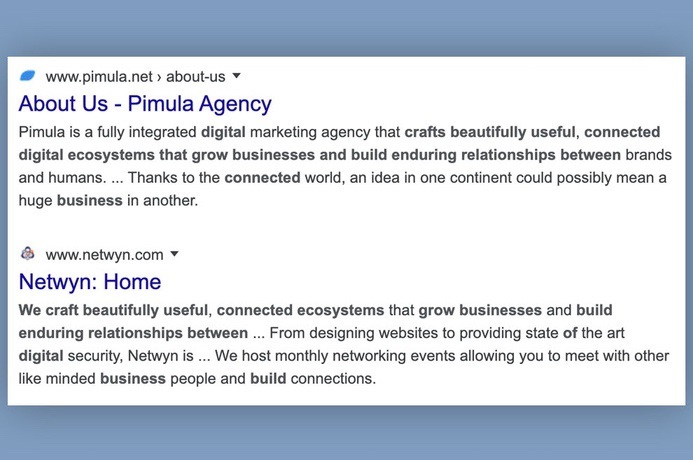

- Digital Forensics: Repurposing Google Analytics IDs

- Russian Bear Attack: Tracking Back the Suspect Origin of a Viral Story

- Apps and Their Affordances for Data Investigations

- A Five Minute Field Guide

- Educator’s Guide: Types of Online Fakes

- Algorithms in the Spotlight: Collaborative Investigations at Spiegel Online

- Your Right to Data

- The #ddj Hashtag on Twitter

- Wobbing Works. Use it!

- Archiving Data Journalism

- From The Guardian to Google News Lab: A Decade of Working in Data Journalism

- Getting Data from the Web

- Data Journalism’s Ties With Civic Tech

- The Web as a Data Source

- Open-Source Coding Practices in Data Journalism

- Crowdsourcing Data at the Guardian Datablog

- Data Feudalism: How Platforms Shape Cross-border Investigative Networks

- How the Datablog Used Crowdsourcing to Cover Olympic Ticketing

- Data-Driven Editorial? Considerations for Working With Audience Metrics

- Using and Sharing Data: the Black Letter, Fine Print, and Reality

- Data Journalism, Digital Universalism and Innovation in the Periphery

- Become Data Literate in 3 Simple Steps

- The Datafication of Journalism: Strategies for Data-Driven Storytelling and Industry–Academy Collaboration

- Data Journalism by, about and for Marginalized Communities

- Tips for Working with Numbers in the News

- Teaching Data Journalism

- Basic Steps in Working with Data

- Organizing Data Projects With Women and Minorities in Latin America

- The £32 Loaf of Bread

- Start With the Data, Finish With a Story

- Genealogies of Data Journalism

- Data Stories

- Data-Driven Gold-Standards: What the Field Values as Award-Worthy Data Journalism and How Journalism Co-Evolves with the Datafication of Society

- Data Journalists Discuss Their Tools of Choice

- Beyond Clicks and Shares: How and Why to Measure the Impact of Data Journalism Projects

- Using Data Visualization to Find Insights in Data

- Data Journalism: In Whose Interests?

- Data Journalism With Impact

- Presenting Data to the Public

- What is Data Journalism For? Cash, Clicks, and Cut and Trys

- How to Build a News App

- Data Journalism and Digital Liberalism

- News Apps at ProPublica

- Visualization as the Workhorse of Data Journalism

- Using visualizations to Tell Stories

- Designing With Data

- Different Charts Tell Different Tales

- Data visualization DIY: Our Top Tools

- How We Serve Data at Verdens Gang

- Public Data Goes Social

- Engaging People Around Your Data

1. The opportunity for using open source information and user-generated content in investigative work

Written by Craig Silverman and Rina Tsubaki

With close to 18,000 followers, the Twitter account @ShamiWitness has been a major source of proIslamic State propaganda. In their investigation of the account, British broadcaster Channel 4 reported that ShamiWitness’ tweets “were seen two million times each month, making him perhaps the most influential Islamic State Twitter account.” Channel 4 also reported that two-thirds of Islamic State foreign fighters on Twitter follow the account.

Channel 4 set out to investigate who was behind the account. All it had to go on was the account and its tweets — the person behind ShamiWitness had never shared personal information or anything that might indicate where they were based.

Simon Israel, the Channel 4 correspondent who led the investigation, said in the report that there were no known photos of ShamiWitness.

“But there are moments — and there are always moments — when the hidden trip up,” he said.

Israel said an analysis of the ShamiWitness account revealed that it used to go by a different handle on Twitter: @ElSaltador. At some point, the account owner changed it to @ShamiWitness.

Channel 4 investigators took that previous Twitter handle and searched other social networks to see if they could find anyone using it. That led them to a Google+ account, and then to a Facebook page. There they found photos and other details about a man living in Bangalore who worked as a marketing executive for an Indian company. Soon, they had him on the phone: He confirmed that he was behind the ShamiWitness account.

The result was an investigative story broadcast in December 2014. That report caused the man behind the Twitter account to stop tweeting.

Channel 4 used publicly available data and information to produce journalism that shut down a key source of propaganda and recruitment for the Islamic State.

Journalists, human rights workers and others are constantly making use of open data, user-generated content and other open source information to produce critically important investigations of everything from conflict zones to human rights abuse cases and international corruption.

“Open source information, which is information freely available to anyone through the Internet — think YouTube, Google Maps, Reddit — has made it possible for ANYONE to gather information and source others, through social media networks,” wrote Eliot Higgins on the Kickstarter campaign page for his open source investigations website, Bellingcat. “Think the Syrian Civil War. Think the Arab Spring.”

The abundance of open source information available online and in databases means that just about any investigation today should incorporate the search, gathering and verification of open source information. This has become inseparable from the work of cultivating sources, securing confidential information and other investigative tactics that rely on hidden or less-public information. Journalists and other who develop and maintain the ability to properly search, discover, analyze and verify this material will deliver better, more comprehensive investigations.

Higgins, who also goes by the pseudonym Brown Moses, is living proof of the power of open source information when combined with dedication and strong verification practices. He has become an internationally recognized expert in the Syrian conflict and the downing of Flight MH17 in Ukraine, to name but two examples. His website, Bellingcat, is where he and others now use open source materials to produce unique and credible investigate work.

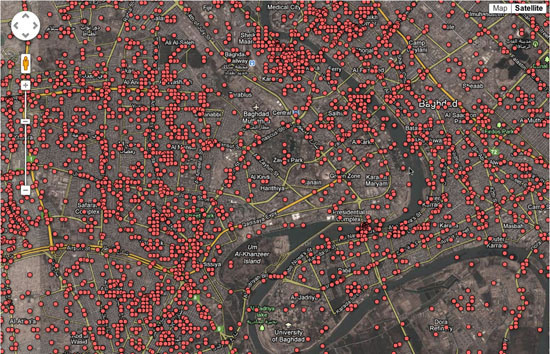

In February 2015, Bellingcat launched a project to track the vehicles being used in the conflict in Ukraine. They invited the public to submit images or footage of military vehicles spotted in the conflict zone, and to help analyze images and footage that had been discovered from social networks and other sources. In its first week of operation, the project added 71 new entries to the vehicles database, almost doubling the amount of information they had previously collected. These were photos, videos and other pieces of evidence that were gathered from publicly available sources, and they told the story of the conflict in a way no one had before.

It’s all thanks to open source information and user-generated content. As chapters and case studies in this Handbook detail, this same material is being used by investigative journalists in Africa and by groups such as Amnesty International and WITNESS to expose fraud, document war crimes and to help the wrongly accused defend themselves in court.

This companion to the original Verification Handbook offers detailed guidance and illustrative case studies to help journalists, human rights workers and others verify and use open source information and user-generated content in service of investigative projects.

With so much information circulating and available on social networks, in public databases and via other open sources, it’s essential that journalists and others are equipped with the skills and knowledge to search, research and verify this information in order to use it in accurate and ethical ways.

This Handbook provides the fundamentals of online search and research techniques for investigations; details techniques for UGC investigations; offers best practices for evaluating and verifying open data; provides workflow advice for fact-checking investigative projects; and outlines ethical approaches to incorporating UGC in investigations.

The initial Verification Handbook focused on verification fundamentals and offered step-by-step guidance on how to verify user-generated content for breaking news coverage. This companion Handbook goes deeper into search, research, fact-checking and data journalism techniques and tools that can aid investigative projects. At the core of each chapter is a focus on enabling you to surface credible information from publicly available sources, while at the same time offering tips and techniques to help test and verify what you’ve found.

As with the verification of user-generated content in breaking news situations, some fundamentals of verification apply in an investigative context. Some of those fundamentals, which were detailed in the original Handbook, are:

- Develop human sources.

- Contact people, and talk to them.

- Be skeptical when something looks, sounds or seems too good to be true.

- Consult multiple, credible sources.

- Familiarize yourself with search and research methods, and new tools.

- Communicate and work together with other professionals — verification is a team sport.

Journalist Steve Buttry, who wrote the Verification Fundamentals chapter in the original Handbook, said that verification is a mix of three elements:

- A person’s resourcefulness, persistence, skepticism and skill

- Sources’ knowledge, reliability and honesty, and the number, variety and reliability of sources you can find and persuade to talk

- Documentation

This Handbook has a particular focus on the third element: documentation. Whether it is using search engines more effectively to gather documentation, examining videos uploaded to YouTube for critical evidence, or evaluating data gathered from an entity or database, it’s essential that investigators have the necessary skills to acquire and verify documentation.

Just as we know that human memory is faulty and that sources lie, we must also remember that documents and data aren’t always what they appear. This Handbook offers some fundamental guidance and case studies to help anyone use open source information and user-generated content in investigations — and to verify that information so that it buttresses an investigation and helps achieve the goal of bringing light to hidden truths.

Foreword

“In today’s digital environment, where rumors and false contents circulate, journal- ists need to be able to actively sort out true, authentic materials from the fakes. This groundbreaking handbook is a must-read for journalists dealing with all types of user generated contents.”

- Wilfried Ruetten, Director, The European Journalism Centre (EJC)

“Accurate information can be a life-saving resource during a humanitarian crisis, but the circumstances from which these crises emerge are typically the most difficult in which to gather reliable information. This book will help not only journalists but anyone working in humanitarian situations in the field to verify facts on the ground.”

- William Spindler, Spokesman, The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)

“This handbook will be essential for journalists covering interreligious and intereth- nic conflicts to report in a more balanced, transparent and accurate way, and ulti- mately help defuse tensions across and within communities.”

- Matthew Hodes, Director, The United Nations Alliance of Civilizations (UNAOC)

“In these times, knowing what is real and how to verify news and other information is essential. This handbook provides essential tools for everyone, journalism and con- sumer.”

- Howard Finberg, Director of Training Partnerships and Alliances, The Poynter Institute

“Getting the facts right is a cardinal principle of journalism but media struggle to be ethical when a big story is breaking. This handbook helps news makers keep faith with truth-telling - even when online speculation is rampant.”

- Aidan White, Director, The Ethical Journalism Network (EJN)

“It’s all about the right information at the right time in the right place. When there is limited access to the disaster-affected areas, it’s crucial for aid workers to gather information via social networks effectively. This handbook would be useful for aid workers working on the ground, as well as online volunteers.”

- Christoph Dennenmoser, Team Lead Urgent Needs, Humanity Road Inc.

Investigating Disinformation and Media Manipulation

Written by: Craig Silverman

Craig Silverman is the media editor of BuzzFeed News, where he leads a global beat covering platforms, online misinformation and media manipulation. He previously edited the “Verification Handbook” and the “Verification Handbook for Investigative Reporting,” and is the author of, "Lies, Damn Lies, and Viral Content: How News Websites Spread (and Debunk) Online Rumors, Unverified Claims and Misinformation."

In December 2019, Twitter user @NickCiarelli shared a video he said showed a dance routine being adopted by supporters of Michael Bloomberg’s presidential campaign. The video’s lackluster enthusiasm and choreography immediately helped it rack up retweets and likes, mostly from people who delighted in mocking it. The video eventually attracted more than 5 million views on Twitter.

Ciarelli’s Twitter bio said he was an intern for the Bloomberg campaign, and his subsequent tweets included proof points such as a screenshot of an email from an alleged Bloomberg campaign staffer approving budget for the video.

But a quick Google search of Ciarelli’s name showed he’s a comedian who has created humor videos in the past. And that email from a Bloomberg staffer? It was sent by Ciarelli’s frequent comedic partner, Brad Evans. That information was also just a Google search away.

But in the first minutes and hours, some believed the cringeworthy video was an official Bloomberg production.

Maggie Haberman, a prominent New York Times political reporter, tweeted that journalists who covered Bloomberg’s previous mayoral campaigns had reason to not dismiss it right away:

Knowledge can take many forms, and in this new digital environment, journalists have to be wary of relying too much on any given source of information — even if it’s their own firsthand experience.

Apparently, some reporters who knew Bloomberg and his style of campaigning felt the video could be real. At the same time, journalists who knew nothing about Bloomberg and chose to judge the video by its source could have found the correct answer immediately — in this case, simply Googling the name of the man who shared it.

The point isn’t that experience covering Bloomberg is bad. It’s that at any given moment we can be led astray by what we think we know. And in some cases our base of knowledge and experience can even be a negative. We can also be fooled by digital signals such as retweets and views, or by efforts to manipulate them.

As the Bloomberg video showed, it takes little effort to create misleading signals like a Twitter bio or a screenshot of an email that appears to back up the content and claim. These in turn help content go viral. And the more retweets and likes it racks up, the more those signals will convince some that the video could be real.

Of course, there are far more devious examples than this one. Unlike Ciarelli, the people behind information operations and disinformation campaigns rarely reveal the ruse. But this case study shows how confusing and frustrating it is for everyone, journalists included, to navigate an information environment filled with easily manipulated signals of quality and trust.

Trust is the foundation of society. It informs and lubricates all transactions and is key to human connection and relationships. But it’s dangerous to operate with default trust in our digital environment.

If your default is to trust that the Twitter accounts retweeting a video are all amplifying it organically, you will get gamed. If you trust that the reviews on a product are all from real customers, you’ll waste your money. If you trust that every news article in your news feed represent an unbiased collection of what you most need to see, you will end up misinformed.

This reality is important for every person to recognize, but it’s essential for journalists. We are being targeted by coordinated and well-funded campaigns to capture our attention, trick us into amplifying messages, and bend us to the will of states and other powerful forces.

The good news is this creates an opportunity — and imperative — for investigation.

This handbook draws on the knowledge and experience of top journalists and researchers to provide guidance on how to execute investigations of digital media manipulation, disinformation and information operations.

We are operating in a complex and rapidly evolving information ecosystem. It requires an equally evolving approach built on testing our assumptions, tracking and anticipating adversaries, and applying the best of open-source investigation and traditional reporting techniques. The vulnerabilities in our digital and data-driven world require journalists to question and scrutinize every aspect of it and apply our skills to help guide the public to accurate, trustworthy information. It also requires journalists to think about how we can unwittingly give oxygen to bad actors and campaigns designed to exploit us, and rush to point fingers at state actors when the evidence does not support it.

The goal of this handbook is to equip journalists with the skills and techniques needed to do this work effectively and responsibly. It also offers basic grounding in the theory, context and mindset that enable journalists to deliver work of high quality that informs the public, exposes bad actors, and helps improve our information environment. But the first thing to understand is that hands-on knowledge and tools are useless unless you approach this work with the right mindset.

This means understanding that everything in the digital environment can be gamed and manipulated, and to recognize the wide variety of people and entities with incentive to do so. The beauty of this environment is that there is often, though not always, a trail of data, interactions, connections and other digital breadcrumbs to follow. And much of it can be publicly available if you know where and how to look.

Investigating the digital means taking nothing at face value. It means understanding that things which appear to be quantifiable and data-driven — likes, shares, retweets, traffic, product reviews, advertising clicks — are easily and often manipulated. It means recognizing that journalists are a key focus of media manipulation and information operations, both in terms of being targeted and attacked, as well as being seen as a key channel to spread mis- and disinformation. And it means equipping yourself and your colleagues with the mindset, techniques and tools necessary to ensure that you’re offering trusted, accurate information — and not amplifying falsehoods, manipulated content or troll campaigns.

At the core of the mindset is the digital investigation paradox: By trusting nothing at first, we can engage in work that reveals what we should and should not trust. And it enables us to produce work that the communities we serve are willing and able to trust.

Along with that, there are some fundamentals that you will see emphasized repeatedly in chapters and case studies:

- Think like an adversary. Each new feature of a platform or digital service can be exploited in some way. It’s critical to put yourself in the shoes of someone looking to manipulate the environment for ideological, political, financial or other reasons. When you look at digital content and messages, you should consider the motivations driving its creation and propagation. It’s also essential to stay abreast of the latest techniques being used by bad actors, digital marketers and others whose livelihood relies on finding new ways to gain attention and earn revenue the digital environment.

- Focus on actors, content, behavior and networks. The goal is to analyze the actors, content and behavior and how they are to document how they might be working in unison as a network. By comparing and contrasting these four things with each other, you can begin to understand what you’re seeing. As you’ll see in multiple chapters and case studies, a fundamental approach is to start with one piece of content or an entity such as a website and pivot on it to identify a larger network through behavior and other connections. This can involve examining the flow of content and actors across platforms, and occasionally into different languages.

- Monitor and collect. The best way to identify media manipulation and disinformation is to look for it all the time. Ongoing monitoring and tracking of known actors, topics and communities of interest is essential. Keep and organize what you find, whether in spreadsheets, screenshot folders or by using paid tools like Hunchly.

- Be careful with attribution. It’s sometimes impossible to say exactly who’s behind a particular account, piece of content, or a larger information operation. One reason is that actors with different motives can behave in similar ways, and produce or amplify the same kind of content. Even the platforms themselves — which have far better access to data and more resources — make attribution mistakes. The most successful and compelling evidence usually combines digital proof with information from inside sources — an ideal mix of online and traditional investigative work. That’s becoming even more difficult as state actors and others evolve and find new ways to hide their fingerprints. Attribution is difficult; getting it wrong will undermine all of the careful work that led up to it.

Finally, a note on the two handbooks that preceded this edition. This work builds on the foundations of the first edition of the Verification Handbook and the Verification Handbook for Investigative Reporting. Each offers fundamental skills for monitoring social media, verifying images, video and social media accounts, and using search engines to identify people, companies and other entities.

Many of the chapters and case studies in this handbook are written with the assumption that readers possess the basic knowledge laid out in these previous publications, particularly the first handbook. If you are struggling to follow along, I encourage you to start with the first handbook.

Now, let’s get to work.

Introduction

Written by: Jonathan W. Y. Gray Liliana Bounegru

Data Journalism in Question

What is data journalism? What is it for? What might it do? What opportunities and limitations does it present? Who and what is involved in making and making sense of it? This book is a collaborative experiment responding to these and other questions.

It follows on from another edited book, The Data Journalism Handbook: How Journalists Can Use Data to Improve the News (O’Reilly Media, 2012). Both books assemble a plurality of voices and perspectives to account for the evolving field of data journalism.

The first edition started through a “book sprint” at MozFest in London in 2011, which brought together journalists, technologists, advocacy groups and others in order to write about how data journalism is done. As we wrote in the introduction, it aimed to “document the passion and enthusiasm, the vision and energy of a nascent movement”, to provide “stories behind the stories” and to let “different voices and views shine through”(Gray et al., 2012).

The 2012 edition is now translated into over a dozen languages – including Arabic, Chinese, Czech, French, Georgian, Greek, Italian, Macedonian, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish and Ukrainian – and is used for teaching at many leading universities, as well as teaching and training centres around the world, as well as being a well-cited source for researchers studying the field.

While the 2012 book is still widely used (and this book is intended to complement rather than to replace it), a great deal has happened since 2012.

On the one hand, data journalism has become more established. In 2011 data journalism as such was very much a field “in the making”, with only a handful of people using the term. It has subsequently become socialised and institutionalised through dedicated organisations, training courses, job posts, professional teams, awards, anthologies, journal articles, reports, tools, online communities, hashtags, conferences, networks, meetups, mailing lists and more.

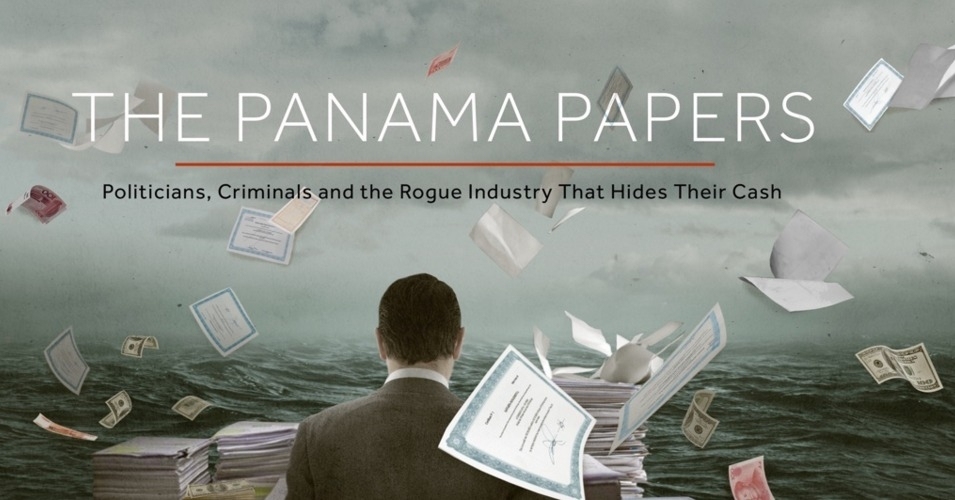

There is also broader awareness of the term through events which are conspicuously data-related, such as the Panama Papers, which whistleblower Edward Snowden then characterised as the “biggest leak in the history of data journalism”(Snowden, 2016).

On the other hand, data journalism has become more contested. The 2013 Snowden leaks helped to establish a transnational surveillance apparatus of states and technology companies as a matter of fact rather than speculation. These leaks suggested how citizens were made knowable through big data practices, showing a darker side to familiar data-making devices, apps and platforms (Gray & Bounegru, 2019).

In the United States the launch of Nate Silver’s dedicated data journalism outlet FiveThirtyEight in 2014 was greeted by a backlash for its overconfidence in particular kinds of quantitative methods and its disdain for “opinion journalism” (Byers, 2014).

While Silver was acclaimed as “lord and god of the algorithm” by The Daily Show’s Jon Stewart for successfully predicting the outcome of the 2012 elections, the statistical methods that he advocated were further critiqued and challenged after the election of Donald Trump in 2016.

These elections along with the Brexit vote in the UK and the rise of populist right-wing leaders around the world, were said to correspond with a “post-truth” moment (Davies, 2016), characterised by a widespread loss of faith in public institutions, expert knowledge and the facts associated with them, and the mediation of public and political life by online platforms which left their users vulnerable to targeting, manipulation and misinformation.1

Whether the so-called “post-truth” moment is taken as evidence of failure or as a call to action, one thing is clear: Data can no longer be taken for granted, and nor can data journalism. Data does not just provide neutral and straightforward representations of the world, but is rather entangled with politics and culture, money and power. Institutions and infrastructures underpinning the production of data – from surveys to statistics, climate science to social media platforms – have been called into question.

At the time of writing, as the COVID-19 pandemic continues to roll on around the world, numbers, graphs and rankings have become widely shared, thematized, politicized and depoliticized—as exemplified by daily circulating epidemiological charts referred to by the now ubiquitous public health strategy to “flatten the curve.”

At the same time, the fragility and provisionality of such data has been widely reported on, with concerns around the under-reporting, non-reporting and classification of cases, as well as growing awareness of the societal and political implications of different kinds of data from sources—from hospital figures to research estimates to self-reporting to transactional data from tracing apps. The pandemic has broadened awareness of not just using but also critically reporting on numbers and data.

Thus one might ask of the use of data in journalism:

-Which data, whose data and by which means?

-Data about which issues and to what end?

-Which kinds of issues are data-rich and which are data-poor, and why?

-Who has the capacity to benefit from data and who doesn’t?

-What kinds of publics does data assemble, which kinds of capacities does it support, what kinds of politics does it enact and what kinds of participation does it engender?

Towards a Critical Data Practice

Rather than bracketing such questions and concerns, this book aims to “stay with the trouble” as the prominent feminist scholar Donna Haraway (2016) puts it.2

Instead of treating the relevance and importance of data journalism as an assertion, we treat this as a question which can be addressed in multiple ways. The collection of chapters gathered in the book aim to provide a richer story about what data journalism does, with and for whom.

Through our editorial work we have encouraged both reflection and a kind of modesty in articulating what data journalism projects can do, and the conditions under which they can succeed.

This entails the cultivation of a different kind of precision in accounting for data journalism practice: specifying the situations in which it develops and operates. Such precision requires broadening the scope of the book to include not just the ways in which data is analysed, created and used in the context of journalism but also more about the social, cultural, political and economic circumstances in which such practices are embedded.

The subtitle of this new book is “towards a critical data practice”, and reflects both our aspiration as editors to bring critical reflection to bear on data journalism practices, as well as reflecting the increasingly critical stances of data journalism practitioners.

The notion of “critical data practice” is a nod to Philip E. Agre’s notion of “critical technical practice”, which he describes in terms of having “one foot planted in the craft work of design and the other foot planted in the reflexive work of critique” (Agre, 1997, p. 155).

As we have written about elsewhere, our interest in this book is understanding how critical engagements with data might modify data practices, making space for public imagination and interventions around data politics (Gray, 2018; Gray et al., 2018).

Alongside contributions from data journalists and practitioners writing about what they do, the book also includes chapters from researchers whose work may advance critical reflection on data journalism practices, from fields such as anthropology, science and technology studies, (new) media studies, internet studies, platform studies, the sociology of quantification, journalism studies, indigenous studies, feminist studies, digital methods and digital sociology.

Rather than assuming a more traditional division of labour such that researchers provide critical reflection and practitioners offer more instrumental tips and advice, we have sought to encourage researchers to consider the practical salience of their work, and to provide practitioners with space to reflect on what they do outside of their day-to-day deadlines.

None of these different perspectives exhaust the field, and our objective is to encourage readers to attend to the different aspects of how data journalism is done. In other words, this book is intended to function as an multidisciplinary conversation starter, and – we hope – a catalyst for collaborations.

We do not assume that “data journalism” refers to a unified set of practices. Rather it is a prominent label which refers to a diverse set of practices which can be empirically studied, specified and experimented with. As one recent review puts it, we need to interrogate the “how of quantification as much as the mere fact of it”, the effects of which “depend on intentions and implementation” (Berman & Hirschman, 2018).

Our purpose is not to stabilise how data journalism is done, but rather to draw attention to its manifold aspects and open up space for doing it differently.

A Collective Experiment

It is worth briefly noting what this book is not. It is not just a textbook or handbook in the conventional sense: the chapters don’t add up to an established body of knowledge, but are rather intended to indicate interesting directions for further inquiry and experimentation.

The book is not just a practical guidebook of tutorials or “how tos”: There are already countless readily available materials and courses on different aspects of data practice (e.g. data analysis and data visualisation). It is not just a book of “behind the scenes” case studies: There are plenty of articles and blog posts showing how projects were done, including interviews with their creators.

It is not just a book of recent academic perspectives: there is an emerging body of literature on data journalism scattered across numerous books and journals.3

Rather, the book has been designed as a collective experiment in accounting for data journalism practices and a collective invitation to explore how such practices may be modified.

It is collective in that, as with the first edition, we have been able to assemble a comparatively large number of contributors (over 70) for a short book. The editorial process has benefitted from recommendations from contributors during email exchanges.

A workshop with a number of contributors at the International Journalism Festival in Perugia in 2018 provided an opportunity for exchanges and reflection. A “beta” version of the book has been released online to provide an opportunity to publicly preview a selection of chapters before the printed version of the book is published and to elicit comments and encounters before the book takes its final shape.

Through what could be considered a kind of curated “snowball editorial”, we have sought to follow how data journalism is done by different actors, in different places, around different topics, through different means. Through the process we have trawled through many shortlists, longlists, outlets and datasets to curate different perspectives on data journalism practices. Although there were many, many more contributors we would have liked to include, we had to operate within the constraints of a printable book, as well as giving voice to a diversity of geographies, themes, concerns and genders.

It is experimental in that the chapters provide different perspectives and provocations on data journalism, which we invite readers to further explore through actively configuring their own blends of tools, data sets, methods, texts, publics and issues. Rather than inheriting the ways of seeing and ways of knowing that have been “baked into” elements such as official data sets or social media data, we encourage readers to enrol them into the service of their own lines of inquiry.

This follows the spirit of “critical analytics” and “inventive methods” which aim to modify the questions which are asked and the way problems are framed (Lury & Wakeford, 2012; Rogers, 2018).

Data journalism can be viewed not just in terms of how things are represented, but in terms of how it organises relations – such that it is not just a matter of producing data stories (through collecting, analysing, visualising and narrating data), but also attending to who and what these stories bring together (including audiences, sources, methods, institutions and social media platforms). Thus we may ask, as Noortje Marres recently put it: “What are the methods, materials, techniques and arrangements that we curate in order to create spaces where problems can be addressed differently?”4.

The chapters in this book show how data journalism can be an inventive, imaginative, collaborative craft, highlighting how data journalists interrogate official data sources, make and compile their own data, try new visual and interactive formats, reflect on the effects of their work and make their methods accountable and code re-usable.

If the future of data journalism is uncertain, then we hope that readers of this book will join us in both critically taking stock of what journalism is and has been, as well as intervening to shape its future. As with all works, the success, failure and ultimate fate of this book-as-experiment ultimately lies with you, its readers, what you do with it, what it prompts and the responses it elicits.

The cover image of this book is a photograph of Sarah Sze’s Fixed Points Finding a Home in the modern art museum Mudam Luxembourg, for which we are most grateful to the artist, her gallery and the museum for their permission to reproduce.5

While it might not seem an obvious choice to put a work of sculpture on the cover of a book about journalism, we thought this image might encourage a relational perspective on data journalism as a kind of curatorial craft, assembling and working with diverse materials, communities and infrastructures to generate different ways of knowing, narrating and seeing the world at different scales and temporalities.

Rather than focusing on the outputs of data journalism (e.g., with screenshots of visualizations or interactives), we wanted to reflect the different kinds of processes and collectives involved in doing journalism with data. Having both serendipitously encountered and been deeply absorbed by Sze’s exhibitions at the Mudam, Venice Biennale, ZKM, the Tate and beyond, we thought her work could provide a different (and hopefully less familiar) vantage point on the practice of data journalism which would resonate with relational perspectives on information infrastructures and “data assemblages.”6

Her installations embody a precise and playful sensibility towards repurposing found materials that visually paralleled what we were hoping to emphasize with our editorial of different accounts of data journalism for the book. Bruno Latour recently wrote that Sze’s approach to assembling materials can be considered to affirm “compositional discontinuities” (Latour, 2020) —which sits well with our hopes to encourage “critical data practice” and to tell stories both with and about the diverse materials and actors involved in data journalism, as we discuss further below, as well as with our editorial approach in supporting the different styles, voices, vernaculars and interests of the chapters in this book.

An Overview of the Book

To stay true to our editorial emphasis on specifying the setting, we note that the orientation of the book and its selection of chapters is coloured by our interests and those of our friends, colleagues and networks at this particular moment—including growing concerns about climate change, environmental destruction, air pollution, tax avoidance, (neo)colonialism, racism, sexism, inequality, extractivism, authoritarianism, algorithmic injustice and platform labour.

The chapters explore how data journalism makes such issues intelligible and experienceable, as well as the kinds of responses it can mobilize. The selection of chapters also reflects our own oscillations between academic research, journalism and advocacy, as well as the different styles of writing and data practice associated with each of these.

We remain convinced of the generative potential of encounters between colleagues in these different fields, and several of the chapters attest to successful cross-field collaborations. As well as exploring synergies and commonalities, it is also worth noting at the outset (as astute readers will notice) that there are differences, tensions and frictions between the perspectives presented in the various chapters, including different histories and origin stories; different views on methods, data and emerging technologies; different views on the desirability of conventionalization and experimentation with different approaches; and different perspectives on what data journalism is, what it is for, its conditions and constraints, how it is organized and the possibilities it presents.

After this introduction, the book starts with a “taster menu” on doing issues with data. This includes a variety of different formats for making sense of different themes in different places—including tracing connections between agricultural commodities, crime, corruption and colonialism across several countries (Sánchez and Villagrán), mapping segregation in the United States (Williams), multiplying memories of trees in Bogotá (Magaña), looking at the people and scenes behind the numbers for home demolitions in occupied East Jerusalem (Haddad), mobilizing for road safety in the Philippines (Rey) and tracking worker deaths in Turkey (Dağ). The chapters in this section illustrate a breadth of practices from visualization techniques to building campaigns to repurposing official data with different analytical priorities.

The second section focuses on how journalists assemble data—an important emerging area which we have sought to foreground in the book and associated research (Gray et al., 2018; Gray & Bounegru, 2019). This includes exploring the making of projects on themes such as knife crime (Barr) and land conflicts (Shrivastava and Paliwal) as well as accounts of how to obtain and work with data in countries where it may be less easy to come by, such as in Cuba (Reyes, Almeida and Guerra) and China (Ma). Assembling data may also be a way of engaging with readers (Coelho) and assembling interested actors around an issue, which may in itself constitute an important outcome of a project. Gathering data may involve the modification of other forms of knowledge production, such as polls and surveys, to the context of journalism (Boros). A chapter on Indigenous data sovereignty (Kukutai and Walter) explores social, cultural and political issues around official data and how to bring other marginalized perspectives to bear on the organization of collective life with data. As well as using numbers as material for telling stories, data journalists may also tell stories about how numbers are made (Verran).

The third section is concerned with different ways of working with data. This includes with algorithms (Stray), code (Simon) and machines (Borges-Rey). Contributors examine emerging issues and opportunities arising from working with sources such as text data (Maseda). Others look at practices for making data journalistic work transparent, accountable and reproducible (Leon; Mazotte). Databases may also afford opportunities for collaborative work on large investigative projects (Díaz-Struck, Gallego and Romera). Feminist thought and practice may also inspire different ways of working with data (D’Ignazio).

The fourth section is dedicated to examining different ways in which data can be experienced, starting with a look at the different formats that data journalism can take (Cohen). Several pieces reflect on contemporary visualization practices (Aisch and Rost), as well as how readers respond to and participate in making sense with visualizations (Kennedy et al.). Other pieces look at how data is mediated and presented to readers through databases (Rahman and Wehrmeyer), web-based interactives (Bentley), TV and radio (de Jong), comics (Luna), and sketching with data (Chalabi and Gray).

The fifth section is dedicated to emerging approaches for investigating data, platforms and algorithms.

Recent journalism projects take the digital as not only offering new techniques and opportunities for journalists, but also new objects for investigation. Examples of this are Bellingcat and BuzzFeed News’ widely shared work on viral content, misinformation and digital culture. 7

Chapters in this section examine different ways of reporting on algorithms (Diakopoulous), as well as how to conduct longer-term collaborations in this area (Elmer). Other chapters look at how to work with social media data to explore how platforms participate in shaping debate, including storytelling approaches (Vo) as well as affinities between digital methods research and data journalism, including how “born digital” data can be used for investigations into web tracking infrastructures (Rogers) as well as about apps and their associated platforms (Weltevrede).

The sixth section is on organizing data journalism, and attends to different types of work in the field which are considered indispensable but not always prominently recognized. This includes how data journalism has changed over the past decade (Rogers); how platforms and the gig economy shape cross-border investigative networks (Cândea); entanglements between data journalism and movements for open data and civic tech (Baack); open-source coding practices (Pitts and Muscato); audience-measurement practices (Petre); archiving data journalism (Broussard); and the role of the #ddj hashtag in connecting data journalism communities on Twitter (Au and Smith).

The seventh section focuses on learning about data journalism as a collaborative process, including data journalism training programmes and the development of data journalism around the world. This includes chapters on teaching data journalism at universities in the United States (Phillips); empowering marginalized communities to tell their stories (Constantaras; Vaca); caution against “digital universalism” and underestimating innova- tion in the “periphery” (Chan); and different approaches for collaborations between journalists and researchers (Radcliffe and Lewis).

Data journalism does not happen in a vacuum. The eighth and final section focuses on situating this practice in relation to its various social, political, cultural and economic settings. A chapter on the genealogies of data journalism in the United States serves to encourage reflection on the various historical practices and ideas which shape it (Anderson). Other chapters look at how data journalism projects are valued through awards (Loosen); different approaches to measuring the impact of data journalism projects (Bradshaw; Green-Barber); issues around data journalism and colonialism (Young and Callison); whether data journalism can live up to its earlier aspirations to become a field of inspired experimentation, interactivity and play (Usher); and data journalism and digital liberalism (Boyer).

Twelve Challenges for Critical Data Practice

Drawing on the time that we have spent exploring data journalism practices through the development of this book, we would like to conclude this introduction to the book with twelve challenges for “critical data practice.”

These consider data journalism in terms of its capacities to shape relations between different actors as well as to produce representations about the world. Having been tested in the context of our “engaged research-led teaching” collaborations at King’s College London and the Public Data Lab,8 they are intended as a prompt for aspiring data journalists, student group projects and investigations, researcher–journalist collaborations, and other activities which aspire to organize collective inquiry with data without taking for granted the infrastructures, environments and practices through which it is produced.

- How can data journalism projects tell stories both with and about data including the various actors, processes, institutions, infrastructures and forms of knowledge through which data is made?

- How can data journalism projects tell stories about big issues at scale (e.g., climate change, inequality, multinational taxation, migration) while also affirming the provisionality and acknowledging the models, assumptions and uncertainty involved in the production of numbers?

- How can data journalism projects account for the collective character of digital data, platforms, algorithms and online devices, including the interplay between digital technologies and digital cultures?

- How can data journalism projects cultivate their own ways of making things intelligible, meaningful and relatable through data, without simply uncritically advancing the ways of knowing “baked into” data from dominant institutions, infrastructures and practices?

- How can data journalism projects acknowledge and experiment with the visual cultures and aesthetics that they draw on, including through combinations of data visualizations and other visual materials?

- How can data journalism projects make space for public participation and intervention in interrogating established data sources and re-imagining which issues are accounted for through data, and how?

- How might data journalists cultivate and consciously affirm their own styles of working with data, which may draw on, yet remain distinct from, areas such as statistics, data science and social media analytics?

- How can the field of data journalism develop memory practices to archive and preserve their work, as well as situating it in relation to practices and cultures that they draw on?

- How can data journalism projects collaborate around transnational issues in ways which avoid the logic of the platform and the colony, and affirm innovations at the periphery?

- How can data journalism support marginalized communities to use data to tell their own stories on their own terms, rather than telling their stories for them?

- How can data journalism projects develop their own alternative and inventive ways of accounting for their value and impact in the world, beyond social media metrics and impact methodologies established in other fields?

- How might data journalism develop a style of objectivity which affirms, rather than minimizes, its own role in intervening in the world and in shaping relations between different actors in collective life?

Words of Thanks

We are most grateful to Amsterdam University Press (AUP), and in particular to Maryse Elliott, for being so supportive with this experimental project, including the publication of an online beta as well as their support for an open access digital version of the book. AUP is perhaps also an apt choice, given that several of the contributors gathered at an early international conference on data journalism which took place in Amsterdam in 2010. Open access funding is supported by a grant from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO, 324-98-014), thanks to Richard Rogers at the University of Amsterdam.

The vision for the book was germinated through discussions with friends and colleagues associated with the Public Data Lab. We particularly benefited from conversations about different aspects of this book with Andreas Birkbak, Erik Borra, Noortje Marres, Richard Rogers, Tommaso Venturini, Esther Weltevrede, Michele Mauri, Gabriele Colombo and Angeles Briones.

We were also provided with space to develop the direction of this book through events and visits to Columbia University (in discussion with Bruno Latour); Utrecht University; the University of California, Berkeley; Stanford University; the University of Amsterdam; the University of Miami; Aalborg University Copenhagen; Sciences Po, Paris; the University of Cambridge; London School of Economics; Cardiff University; Lancaster University; and the International Journalism Festival in Perugia.

Graduate students taking the MA course in data journalism at King’s College London helped us to test the notion of “critical data practice” which lies at the heart of this book. Our longstanding hope to do another edition was both nurtured and materialized thanks to Rina Tsubaki, who helped to facilitate support from the European Journalism Centre and the Google News Lab. We are grateful to Adam Thomas, Bianca Lemmens, Biba Klomp, Letizia Gambini, Arne Grauls and Simon Rogers for providing us with both editorial independence and enduring support to scale up our efforts.

The editorial assistance of Daniela Demarchi and Oana Bounegru has been tremendously valuable in helping us to chart a clear course through sprawling currents of texts, footnotes, references, emails, shared documents, version histories, spreadsheets and other materials.

Most of all, we would like to thank all of the data journalism practitioners and researchers who were involved in the project (whether through writing, correspondence or discussion) for accompanying us, and for supporting this experiment with their contributions of time, energy, materials and ideas without which the project would not have been possible. This book is, and continues to be, a collective undertaking.

Footnotes

1. For a critical perspective on this term, see Jasanoff, S., & Simmet, H. R. (2017). No funeral bells: Public reason in a “post-truth” age. Social Studies of Science, 47(5), 751–770.

2. Alluding to this work, Verran’s chapter in this book explores how data journalists might stay with the trouble of value and numbers.

3. www.zotero.org/groups/data_journalism_research

4. A question that Noortje Marres asked in her plenary contribution to EASST 2018 in Lancaster: twitter.com/jwyg/status/1023200997668204544

5. Sarah Sze,Fixed Points Finding a Home, 2012 (details). Mixed media. Dimensions variable. Mudam Luxembourg Commission and Collection. Donation 2012—Les Amis des Musées d’Art et d’Histoire Luxembourg. © Artwork: Sarah Sze. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro. © Photo: Andrés Lejona/Mudam Luxembourg.

6. For relational perspectives on data infrastructures see, for example, the seminal work of Susan Leigh Star: Star, S. L., & Ruhleder, K. (1996). Steps toward an ecology of infrastructure: Design and access for large information spaces.Information Systems Research, 7, 111–134; Star, S. L. (1999). The ethnography of infrastructure. American Behavioral Scientist, 43, 377–391. For more recent work on “data assemblages,” see, for example: Kitchin, R. (2014). The data Big data, open data, data infrastructures and their consequences. SAGE; Kitchin, R., & Lauriault,T. (2018). Towards critical data studies: Charting and unpacking data assemblages and their work. In J. Thatcher, A. Shears, & J. Eckert (Eds.), Thinking big data in geography: New regimes, new research (pp. 3–20). University of Nebraska Press.

7. www.buzzfeednews.com/topic/fake-news, www.bellingcat.com

8. www.kcl.ac.uk/research/engaged-research-led-teaching and publicdatalab.org

Works Cited

Agre, P. E. (1997). Toward a critical technical practice: Lessons learned in trying to reform AI. In G. Bowker, S. L. Star, B. Turner, & L. Gasser (Eds.), Social science, techni- cal systems, and cooperative work: Beyond the great divide (pp. 130–157). Erlbaum.

Berman, E. P., & Hirschman, D. (2018). The sociology of quantif ication: Where are we now? Contemporary Sociology, 47(3), 257–266. doi.org/10.1177/0094306118767649

Byers, D. (2014, March 19). Knives out for Nate Silver. Politico. www.politico.com/blogs/media/2014/03/knives-out-for-nate-silver-185394.html

Davies, W. (2016, August 24). The age of post-truth politics. The New York Times. www.nytimes.com/2016/08/24/opinion/campaign-stops/the-age-of-post-truth-politics.html

Gray, J. (2018). Three aspects of data worlds. Krisis: Journal for Contemporary Philosophy, 1.

Gray, J., & Bounegru, L. (2019). What a difference a dataset makes? Data journalism and/as data activism. In J. Evans, S. Ruane, & H. Southall (Eds.), Data in society: Challenging statistics in an age of globalisation (pp. 365-374). The Policy Press. doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1415450

Gray, J., Chambers, L., & Bounegru, L. (Eds.). (2012). The data journalism handbook: How journalists can use data to improve the news. O’Reilly Media.

Gray, J., Gerlitz, C., & Bounegru, L. (2018). Data infrastructure literacy. Big Data & Society, 5(2), 1–13. doi.org/10.1177/2053951718786316

Haraway, D. J. (2016). Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press. doi.org/10.1215/9780822373780

Latour, B. (2020) Sarah Sze as the sculptor of Critical Zones. In B. Latour & P. Weibel (Eds.), Critical zones: The science and politics of landing on earth (pp. 158–159). The MIT Press.

Lury, C., & Wakeford, N. (Eds.). (2012). Inventive methods: The happening of the social. Routledge.

Rogers, R. (2018). Otherwise engaged: Social media from vanity metrics to critical analytics. International Journal of Communication, 12, 450–472. dare.uva.nl/search?identifier=e7a7c11b-b199-4d7c-a9cb-fdf1dd74d493

Snowden, E. (2016, April 3). Biggest leak in the history of data journalism just went live, and it’s about corruption. Twitter. twitter.com/Snowden/status/716683740903247873

For the Great Unnamed

Written by: Liliana Bounegru , Lucy Chambers , Jonathan W. Y. Gray

The Data Journalism Handbook was born at a 48 hour workshop at MozFest 2011 in London. It subsequently spilled over into an international, collaborative effort involving dozens of data journalism’s leading advocates and best practitioners.

In the 6 months that passed between the book’s inception to its first full release, hundreds of people have contributed in various ways. While we have done our best to keep track of them all, we have had our fair share of anonymous, pseudonymous and untraceable edits.

To all of those people who have contributed and are not listed below, we say two things. Firstly, thank you. Secondly, can please tell us who you are so that we can give credit where credit is due.

2. Using online research methods to investigate the Who, Where and When of a person

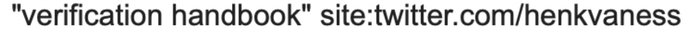

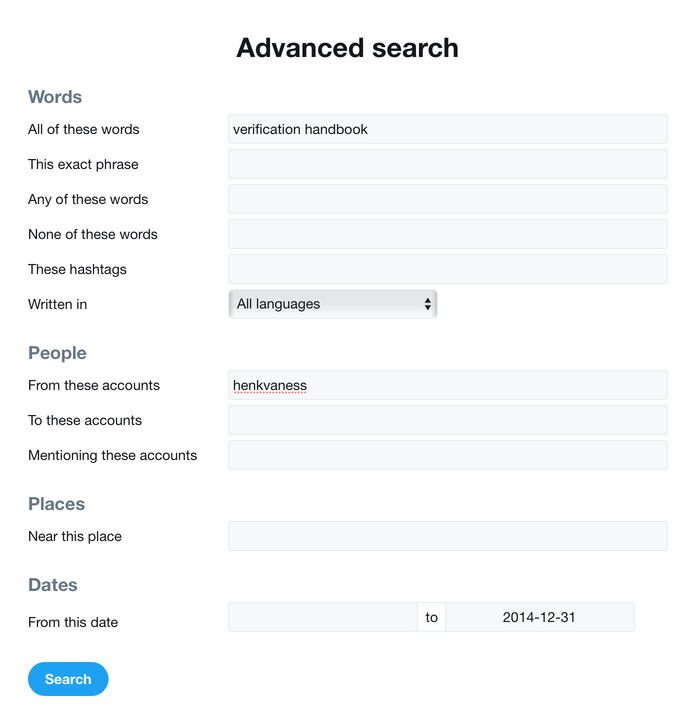

Written by Henk van Ess

Online research is often a challenge for traditional investigative reporters, journalism lecturers and students. Information from the web can be fake, biased, incomplete or all of the above.

Offline, too, there is no happy hunting ground with unbiased people or completely honest governments. In the end, it all boils down to asking the right questions, digital or not. This chapter gives you some strategic advice and tools for digitizing three of the biggest questions in journalism: who, where and when?

1. Who?

Let’s do a background profile with Google on Ben van Beurden, CEO of the Shell Oil Co.

a. Find facts and opinions

The simple two-letter word “is” reveals opinions and facts about your subject. To avoid clutter, include the company name of the person or any other detail you know, and tell Google that both words should be not that far from each other.

The AROUND() operator MUST BE IN CAPITALS. It sets the maximum distance in words between the two terms.

b. What do others say?

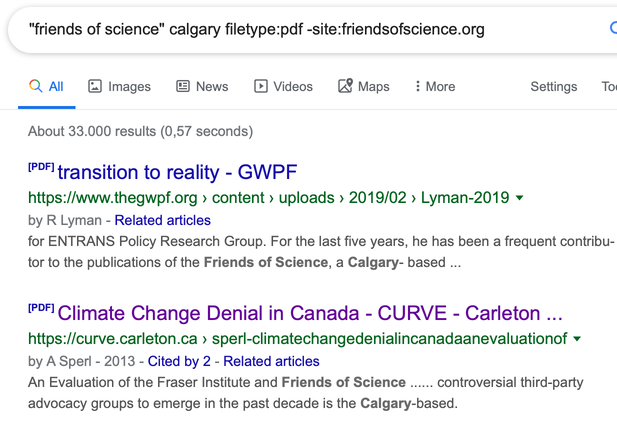

This search is asking Google to “Show me PDF documents with the name of the CEO of Shell in it, but exclude documents from Shell.” This will find documents about your subject, but not from the company of the subject itself. This helps you to see what opponents, competitors or opinionated people say about your subject. If you are a perfectionist, go for

inurl:pdf “ben van beurden” –site:shell.*

because you will find also PDFs that are not visible with filetype.

c. Official databases

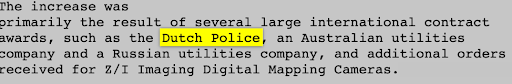

Search for worldwide official documents about this person. It searches for gov.uk (United Kingdom) but also .gov.au (Australia), .gov.cn (China), .gov (U.S.) and other governmental websites in the world. If you don’t have a .gov website in your country, use the local word for it with the site: operator. Examples would be site:bund.de (Germany) or site:overheid.nl (The Netherlands).

With this query, we found van Beurden’s planning permission for his house in London, which helped us to find his full address and other details.

d. United Nations

You are now searching in any United Nations-related organization. In this example, we find the Shell CEO popping up in a paper about “Strategic Approach to International Chemicals Management.” And we found his full name, the name of his wife, and his passport number at the time when we did this search. Amazing.

e. Find the variations

With this formula you can find result that use different spellings of the name. You will receive documents with the word Shell, but not those that include “Ben” as the first name. With this, you will find out that he is also referred to as Bernardus van Beurden. (You don’t need to enter a dot [.] because Google will ignore points.) Now repeat steps a, b, c and d with this new name.

2. Where

a. Use photo search in Topsy

You can use http://topsy.thisisthebrigade.com to find out where your subject was, by analyzing his mentions (1) over time (2) and by looking at the photos (3) that others posted on Twitter. If you’d rather research a specific period, go for “Specific Range” in the time menu.

b. Use Echosec

With Echosec, you can search social media for free. In this example, I entered the address of Shell HQ (1) in hopes of finding recent (2) postings from people who work there (3).

c. Use photo search in Google Images

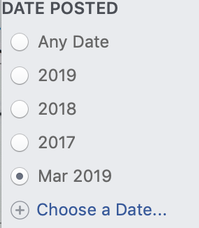

Combine all you know about your subject in one mighty phrase. In the below example, I’m searching for a jihadist called @MuhajiriShaam (1) but not the account @MuhajiriShaam01 (2) on Twitter (3). I just want to see the photos he posted on Twitter between Sept. 25 and Sept. 29, 2014 (4).

3. When

a. Date search

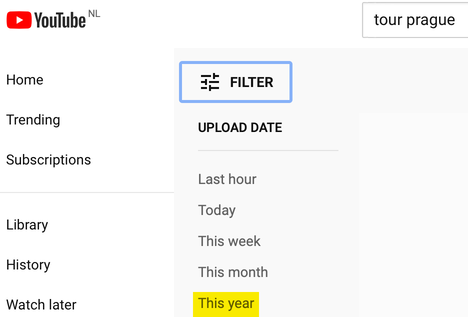

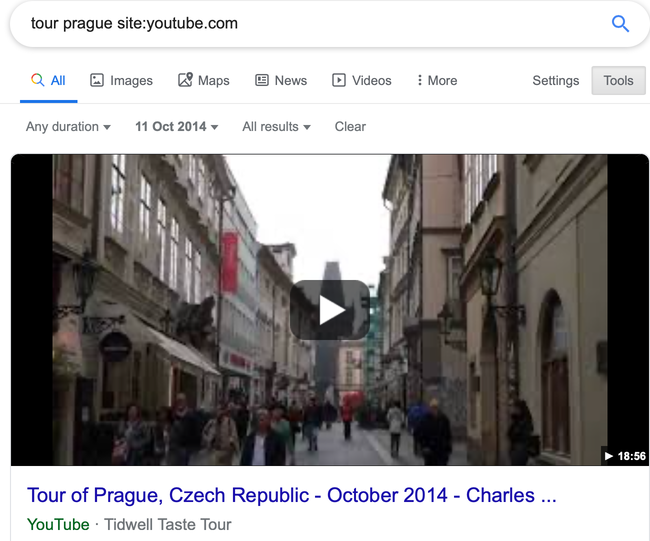

Most of the research you do is not based on today, but an earlier period. Always tell your search engine this. Go back in time.

Let’s investigate a fire in a Dutch chemical plant called Chemie-Pack. The fire happened on Jan. 5, 2011. Perhaps you want to investigate if dangerous chemicals were stored at the plant. Go to images.google.com, type in Chemie-pack (1) and just search before January 2011 (2). The results offer hundreds of photos from a youth fire department that visited the company days before the fire. In some photos, you can see barrels with names of chemicals on them. We used this to establish which chemicals were stored in the plant days before the fire.

b. Find old data with archive.org

Websites often cease to exist. There is a chance you can still view them by using archive.org. This tool can do its work only if you know the URL of the webpage you want to see. The problem is that often the link is gone and therefore you don’t know it. So how do you find a seemingly disappeared URL?

Let’s assume we want to find the home page of a dead actress called Lana Clarkson.

Step One: Find an index

Find a source about the missing page. In this case, we can use her Wikipedia page.

Step Two: Put the index in the time machine

Go to archive.org and enter the URL of her Wikipedia page, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lana_Clarkson. Choose the oldest available version, March 10, 2004. There it says the home page was http://www.lanaclarkson.com.

Step Three: Find the original website

Now type the link in archive.org, but add a backslash and an asterisk to the URL: https://web.archive.org/web/*/http://www.lanaclarkson.com/*

All filed links are now visible. Unfortunately, in this case, you won’t find that much. Clarkson became famous only after her death. She was shot and killed by famed music producer Phil Spector in February 2003.

Contributor List

The following people have drafted or otherwise directly contributed to text which is in the current version of the book. The illustrations are by graphic designer Kate Hudson.

-

Gregor Aisch, Open Knowledge Foundation

-

Brigitte Alfter, Journalismfund.eu

-

David Anderton, Freelance Journalist

-

James Ball, The Guardian

-

Caelainn Barr, Citywire

-

Mariana Berruezo, Hacks/Hackers Buenos Aires

-

Michael Blastland, Freelance Journalist

-

Mariano Blejman, Hacks/Hackers Buenos Aires

-

John Bones, Verdens Gang

-

Marianne Bouchart, Bloomberg News

-

Liliana Bounegru, European Journalism Centre

-

Brian Boyer, Chicago Tribune

-

Paul Bradshaw, Birmingham City University

-

Wendy Carlisle, Australian Broadcasting Corporation

-

Lucy Chambers, Open Knowledge Foundation

-

Sarah Cohen, Duke University

-

Alastair Dant, The Guardian

-

Helen Darbishire, Access Info Europe

-

Chase Davis, Center for Investigative Reporting

-

Steve Doig, Walter Cronkite School of Journalism of Arizona State University

-

Lisa Evans, The Guardian

-

Tom Fries, Bertelsmann Stiftung

-

Duncan Geere, Wired UK

-

Jack Gillum, Associated Press

-

Jonathan Gray, Open Knowledge Foundation

-

Alex Howard, O’Reilly Media

-

Bella Hurrell, BBC

-

Nicolas Kayser-Bril, Journalism++

-

John Keefe, WNYC

-

Scott Klein, ProPublica

-

Alexandre Léchenet, Le Monde

-

Mark Lee Hunter, INSEAD

-

Andrew Leimdorfer, BBC

-

Friedrich Lindenberg, Open Knowledge Foundation

-

Mike Linksvayer, Creative Commons

-

Mirko Lorenz, Deutsche Welle

-

Esa Mäkinen, Helsingin Sanomat

-

Pedro Markun, Transparência Hacker

-

Isao Matsunami, Tokyo Shimbun

-

Lorenz Matzat, OpenDataCity

-

Geoff McGhee, Stanford University

-

Philip Meyer, Professor Emeritus, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

-

Claire Miller, WalesOnline

-

Cynthia O’Murchu, Financial Times

-

Oluseun Onigbinde, BudgIT

-

Djordje Padejski, Knight Journalism Fellow, Stanford University

-

Jane Park, Creative Commons

-

Angélica Peralta Ramos, La Nacion (Argentina)

-

Cheryl Phillips, The Seattle Times

-

Aron Pilhofer, New York Times

-

Lulu Pinney, Freelance Infographic Designer

-

Paul Radu, Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project

-

Simon Rogers, The Guardian

-

Martin Rosenbaum, BBC

-

Amanda Rossi, Friends of Januária

-

Martin Sarsale, Hacks/Hackers Buenos Aires

-

Fabrizio Scrollini, London School of Economics and Political Science

-

Sarah Slobin, Wall Street Journal

-

Sergio Sorin, Hacks/Hackers Buenos Aires

-

Jonathan Stray, The Overview Project

-

Brian Suda, (optional.is)

-

Chris Taggart, OpenCorporates

-

Jer Thorp, The New York Times R&D Group

-

Andy Tow, Hacks/Hackers Buenos Aires

-

Luk N. Van Wassenhove, INSEAD

-

Sascha Venohr, Zeit Online

-

Jerry Vermanen, NU.nl

-

César Viana, University of Goiás

-

Farida Vis, University of Leicester

-

Pete Warden, Independent Data Analyst and Developer

-

Chrys Wu, Hacks/Hackers

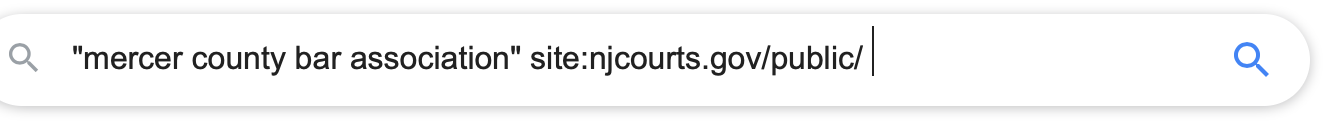

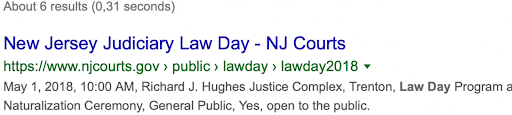

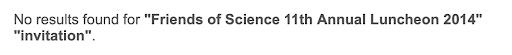

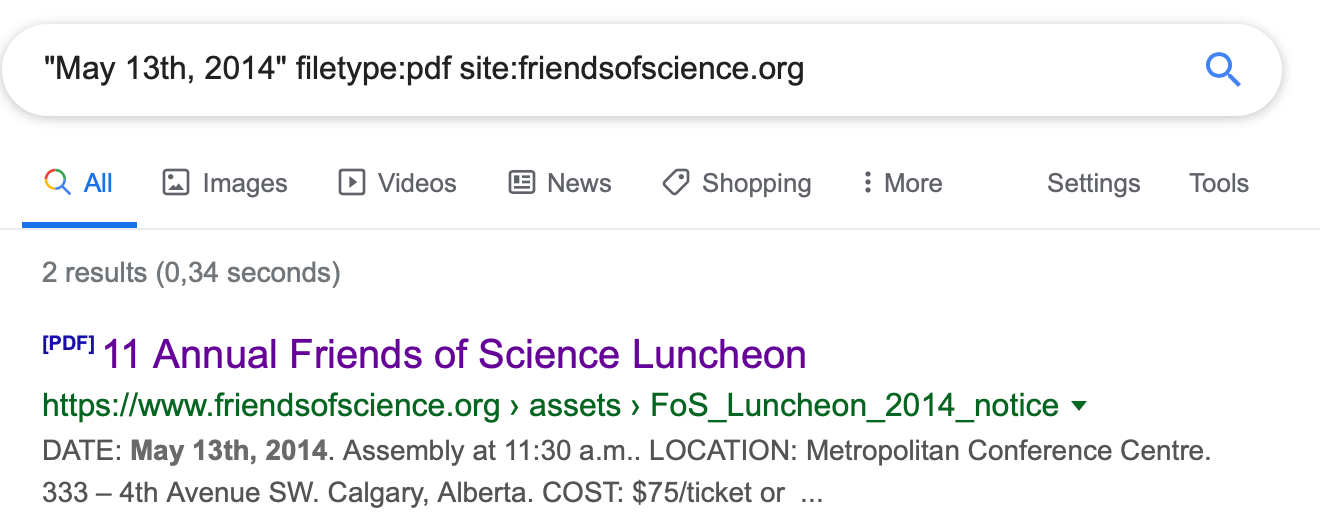

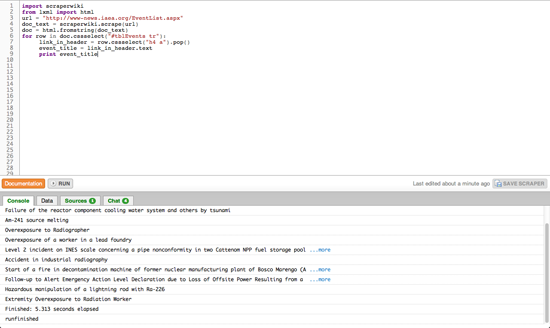

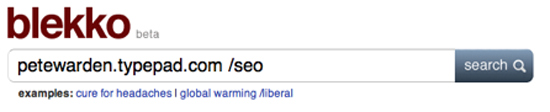

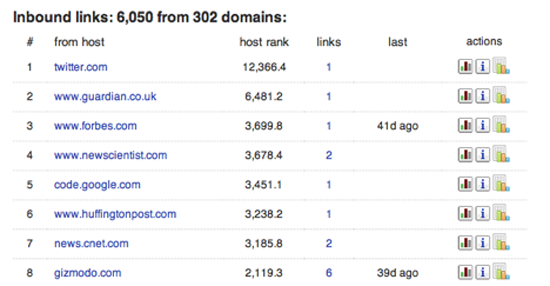

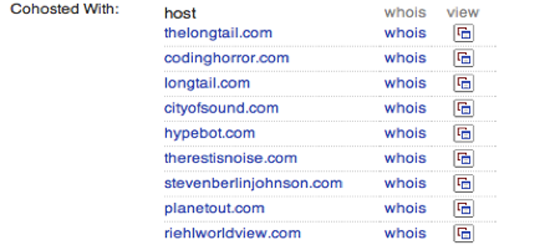

3. Online research tools and investigation techniques

Written by Paul Myers

Search engines are an intrinsic part of the array of commonly used “open source” research tools. Together with social media, domain name look-ups and more traditional solutions such as newspapers and telephone directories, effective web searching will help you find vital information to support your investigation.

Many people find that search engines often bring up disappointing results from dubious sources. A few tricks, however, can ensure that you corner the pages you are looking for, from sites you can trust. The same goes for searching social networks and other sources to locate people: A bit of strategy and an understanding of how to extract what you need will improve results.

This chapter focuses on three areas of online investigation:

1. Effective web searching.

2. Finding people online.

3. Identifying domain ownership.

1. Effective web searching

Search engines like Google don’t actually know what web pages are about. They do, however, know the words that are on the pages. So to get a search engine to behave itself, you need to work out which words are on your target pages.

First off, choose your search terms wisely. Each word you add to the search focuses the results by eliminating results that don’t include your chosen keywords.

Some words are on every page you are after. Other words might or might not be on the target page. Try to avoid those subjective keywords, as they can eliminate useful pages from the results.

Use advanced search syntax.

Most search engines have useful so-called hidden features that are essential to helping focus your search and improve results.

Optional keywords

If you don’t have definite keywords, you can still build in other possible keywords without damaging the results. For example, pages discussing heroin use in Texas might not include the word “Texas”; they may just mention the names of different cities. You can build these into your search as optional keywords by separating them with the word OR (in capital letters).

You can use the same technique to search for different spellings of the name of an individual, company or organization.

Search by domain

You can focus your search on a particular site by using the search syntax “site:” followed by the domain name.

For example, to restrict your search to results from Twitter:

To add Facebook to the search, simply use “OR” again:

You can use this technique to focus on a particular company’s website, for example. Google will then return results only from that site.

You can also use it to focus your search on municipal and academic sources, too. This is particularly effective when researching countries that use unique domain types for government and university sites

Note: When searching academic websites, be sure to check whether the page you find is written or maintained by the university, one of its professors or one of the students. As always, the specific source matters.

Searching for file types

Some information comes in certain types of file formats. For instance, statistics, figures and data often appear in Excel spreadsheets. Professionally produced reports can often be found in PDF documents. You can specify a format in your search by using “filetype:” followed by the desired data file extension (xls for spreadsheet, docx for Word documents, etc.).

2. Finding people

Groups can be easy to find online, but it’s often trickier to find an individual person. Start by building a dossier on the person you’re trying to locate or learn more about. This can include the following:

- The person’s name, bearing in mind:

- Different variations (does James call himself “James,” “Jim,” “Jimmy” or “Jamie”?).

- The spelling of foreign names in Roman letters (is Yusef spelled “Yousef” or “Yusuf”?).

- Did the names change when a person married?

- Do you know a middle name or initial?

- The town the person lives in and or was born in.

- The person’s job and company.

- Their friends and family members’ names, as these may appear in friends and follower lists.

- The person’s phone number, which is now searchable in Facebook and may appear on web pages found in Google searches.

- Any of the person’s usernames, as these are often constant across various social networks.

- The person’s email address, as these may be entered into Facebook to reveal linked accounts. If you don’t know an email address, but have an idea of the domain the person uses, sites such as email-format can help you guess it.