Navigating vaccine hesitancy

Conversations with Data: #64

Do you want to receive Conversations with Data? Subscribe

Welcome to the final Conversations with Data newsletter of 2020.

With COVID-19 vaccine programmes rolling out in the United Kingdom and the United States this month, vaccine misinformation continues to be a growing problem globally.

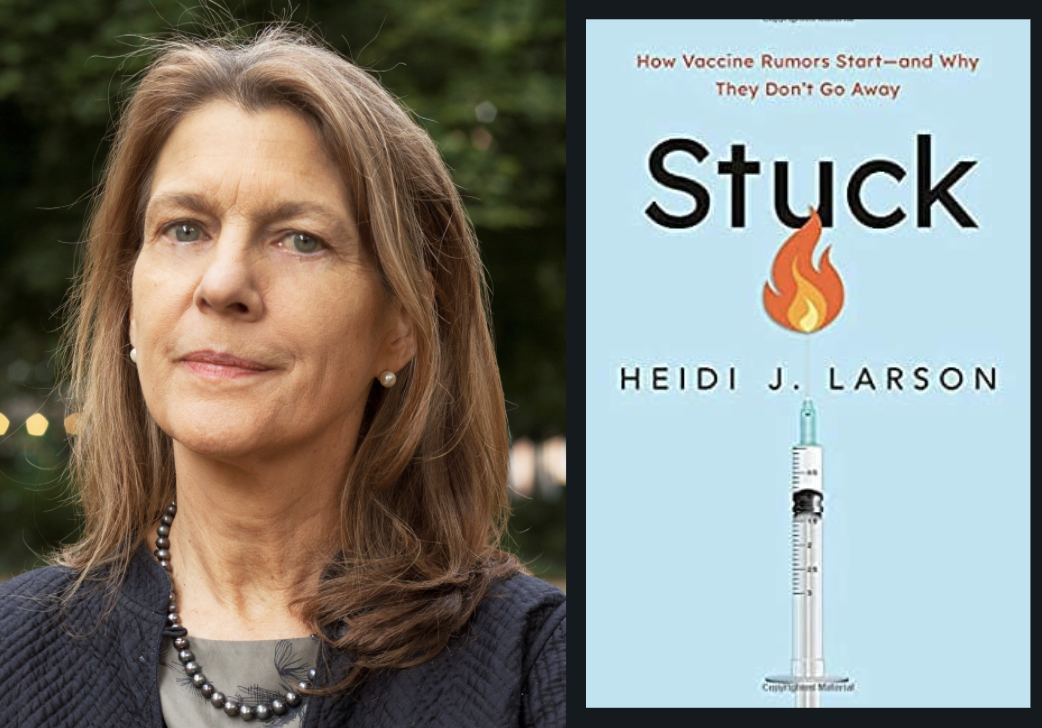

To help journalists better understand this, our latest Conversations with Data podcast features an interview with Professor Heidi Larson, the founder and director of the Vaccine Confidence Project at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. In addition to vaccine hesitancy, she talks to us about her new book, "Stuck: How Vaccine Rumors Start and Why They Don't Go Away".

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, SoundCloud or Apple Podcasts. Alternatively, read the edited Q&A with Professor Heidi Larson below.

What we asked

Tell us about your career. How did you become interested in vaccines as an anthropologist?

I didn't set out in anthropology to study vaccines, but I was always interested in health and ended up spending most of my career working in health. I had worked a lot in AIDS and saw how powerful non-medical interventions were. I later moved into vaccines and headed Global Immunisation Communication at UNICEF. After I left UNICEF, I set up the Vaccine Confidence Project to measure it globally. This involved looking at the types of concerns, developing an index and designing some metrics around this complicated space.

Based on the Vaccine Confidence Project's newly published survey findings, what trends are you seeing around the world?

We just released our global trends in vaccine confidence research in The Lancet in September 2020. The new study mapped global trends in vaccine confidence across 149 countries between 2015 and 2019 using data from over 284,000 adults. The respondents were surveyed about their views on whether vaccines are important, safe, and effective.

What's interesting is that we see Europe got a little bit better, particularly in Finland, France, Ireland, and Italy. We see countries in Northern Africa are becoming more sceptical. We see countries in South America that historically have been like the poster child of vaccine enthusiasm have been wearing at the edges. The research shows how diverse it is regionally and it gives an interesting map.

Professor Heidi Larson is an anthropologist and the founding director of the Vaccine Confidence Project. She headed Global Immunisation Communication at UNICEF and she is the author of "Stuck: How Vaccine Rumors Start and Why They Don't Go Away".

Tell us about your book "Stuck". Who did you have in mind when writing the book?

I had the whole world in mind when writing this. I was playing with "stuck" like an injection, but also "stuck" in the conversation. The book is reflecting on the last 10 to 20 years of my own research and examines how the issues surrounding vaccine hesitancy are, more than anything, about people feeling left out of the conversation. "Stuck" provides a clear-eyed examination of the social vectors that transmit vaccine rumours, their manifestations around the globe, and how these individual threads are all connected.

How likely is it that these new COVID-19 vaccines will stamp out this virus?

Well, it depends on how many people are willing to take the vaccines. I hear estimates from 60 to 70 percent are needed. Some say a bit more. Some say a bit less for the amount of uptake to actually have any kind of population benefit in protecting people against COVID-19. If it doesn't reach that, many individuals will benefit from it, but it won't have that same kind of population benefit.

The surveys we're seeing globally are not showing those high levels of acceptance. You don't know until the vaccine is ready what people do. I mean, look at political opinion polling. People can change their mind there. We still don't have the final information on these vaccines. We've got some indication of how effective they might be. But we're still waiting for more information. And it's going to come.

Many people are concerned about how quickly this vaccine has been developed. But that doesn't mean it hasn't gone through the same safety measures and three-stage trialling as other vaccines, right?

That's true. But as you say, a different context. When the West Africa Ebola outbreak happened, the global health and scientific community realised there was no emergency funding for research trials. There was emergency funding for control measures in treating and isolating it, but there wasn't for trials. So because of that, there was a funding mechanism, Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovation (CEPI) that was ready to fund these COVID-19 trials, which we've never had before. This meant trials could get up and running much quicker.

We also have a lot of new technologies that were not used in previous vaccine development, which have allowed different kinds of processes to move quickly. Administrative processes have shortened a bit. Safety measures have not. That is the one piece of the development that has not shortened. Nobody wants to compromise safety. It would be bad for industry. It would be bad for government. It would be bad for populations. It's in nobody's interest to make a vaccine that is not safe.

What can journalists do to stop the spread of vaccine misinformation?

I think that we have to be careful with deleting the misinformation without putting something else in that space. The reason people migrate to misinformation is that they aren't finding the answers to their questions. So we should use and listen to misinformation to understand what are the kinds of issues that people are trying to find information for. Because if people are all migrating to certain pieces of misinformation, they're not getting what they need somewhere else.

So let's not delete it without giving an alternative story. I think that from a journalistic point of view, that's really important. Talk about why it's shorter. Just keep people engaged in a positive, informed way and don't just leave the space empty. Otherwise, they'll go right back to where they got the misinformation in the first place.

What role do social media platforms have in fighting vaccine misinformation?

I think one of the bigger challenges is the posts on social media that are not explicitly misinformation. They're seeding doubt and dissent. They're asking questions. They're provoking a highly sceptical population. And that's a much harder thing to handle. You can't delete doubt. That's one of the things I'm working very closely with Facebook on -- looking at different ways to rein it in -- at least mitigate the impact of it. Before we wag our fingers at any one social media platform or all of them, I think we certainly, as a global health community, need to do a better job of engaging publics and getting them the right information so they're not going off looking for another story.

Finally, what other credible resources can you recommend for journalists?

You can visit our website VaccineConfidence.org. Another excellent resource is the Vaccine Safety Net, a global network of websites, established by the World Health Organisation, that provides reliable information on vaccine safety. It reviews and approves websites and we're one of their websites that they review and say is credible.

What I like about the Vaccine Safety Net is that it gives you a choice and people want a choice. That's been a real problem in general with the pro-vaccine rhetoric sentiment. It's very homogenous compared to the anti-vaccine movement, which has a lot of different flavours and colours. And so for the public, with their multitude of different concerns and different anxieties, they have a lot to choose from.

Don't miss our latest long reads on DataJournalism.com

Finding hidden data inside the world's free encyclopedia is no easy task for journalists. In Monika Sengul-Jones' long read article, she explains how to navigate the often unwieldy world of Wikipedia.

Our next conversation

Our first Conversations with Data podcast of 2021 will feature an interview with Sam Dubberley, head of the Crisis Evidence Lab at Amnesty International. He will talk to us about his work managing the Digital Verification Corps and the evolution of open source investigations for human rights advocacy.

Sam is a fellow of the Human Rights Centre at the University of Essex where he is a research consultant for their Human Rights Big Data and Technology Project. He is also the co-editor of the book "Digital Witness: Using Open Source Information for Human Rights Investigation, Documentation, and Accountability".

As always, don’t forget to let us know what you’d like us to feature in our future editions. You can also read all of our past editions here.

Onwards!

Tara from the EJC Data team,

bringing you DataJournalism.com, supported by Google News Initiative.

P.S. Are you interested in supporting this newsletter as well? Get in touch to discuss sponsorship opportunities.

Time to have your say

Sign up for our Conversations with Data newsletter

Join 10.000 data journalism enthusiasts and receive a bi-weekly newsletter or access our newsletter archive here.

Almost there...

If you experience any other problems, feel free to contact us at [email protected]