8. Investigating websites

Written by: Craig Silverman

Craig Silverman is the media editor of BuzzFeed News, where he leads a global beat covering platforms, online misinformation and media manipulation. He previously edited the “Verification Handbook” and the “Verification Handbook for Investigative Reporting,” and is the author of “Lies, Damn Lies, and Viral Content: How News Websites Spread (and Debunk) Online Rumors, Unverified Claims and Misinformation.”

Websites are used by those engaged in media manipulation to earn revenue, collect emails and other personal information, or otherwise establish an online beachhead. Journalists must understand how to investigate a web presence, and, when possible, connect it to a larger operation that may involve social media accounts, apps, companies or other entities.

Remember that text, images or the entire site itself may disappear over time — especially after you start contacting people and asking questions. A best practice is to use the Wayback Machine to save important pages on your target website as part of your workflow. If a page won’t save properly there, use a tool such as archive.today. This ensures you can link to archived pages as proof of what you found, and avoid directly linking to a site spreading mis/disinformation. (Hunchly is a great paid tool for creating your own personal archive of webpages automatically while you work.) These archiving tools are also essential for investigating what a website has looked like over time. I also recommend installing the Wayback Machine browser extension so it’s easy to archive pages and look at earlier versions.

Another useful browser extension is Ghostery, which will show you the trackers present on a webpage. This helps you quickly identify whether a site uses Google Analytics and/or Google AdSense IDs, which will help with one of the techniques outlined below.

This chapter will look at four categories to analyze when investigating a website: content, code, analytics, registration and connected elements.

Content

Most websites tell you at least a bit about what they are. Whether on a dedicated About page, a description in the footer or somewhere else, this is a good place to start. At the same time, a lack of clear information could be a hint the site was created in haste, or is trying to conceal details about its ownership and purpose.

Along with reading any basic “about” text, perform a thorough review of content on a website, with an eye toward determining who’s running it, what the purpose is, and whether it’s part of a larger network or initiative. Some things to look for:

- Does it identify the owner or any corporate entity on its about page? Also note if it doesn’t have an About page.

- Does it list a company or person in a copyright notice at the very bottom of the homepage or any other page?

- Does it list any names, addresses or corporate entities in the privacy policy or terms and conditions? Are those names or companies different from what’s listed on the footer, about page or other places on the site?

- If the site publishes articles, note the bylines and if they are clickable links. If so, see if they lead to an author page with more information, such as a bio or links to the writer’s social accounts.

- Does the site feature related social accounts? These could be in the form of small icons at the top, bottom or side of the homepage, or an embed inviting you to like its Facebook page, for example. If the page shows icons for platforms such as Facebook and Twitter, hover your mouse over them and look at the bottom left of your browser window to see the URL they lead to. Often, a hastily created website will not bother to fill in the specific social profile IDs in a website’s template. In that case, you’ll just see the link show up as facebook.com/ with no username.

- Does the site list any products, clients, testimonials or other people or companies that may have a connection and be worth looking into?

- Be sure to dig beyond the homepage. Click on all main menus and scroll down to the footer to find other pages worth visiting.

An important part of examining the content is to see if it’s original. Has text from the site’s About page or other general text been copied from elsewhere? Is the site spreading false or misleading information, or helping push a specific agenda?

In 2018 I investigated a large digital advertising fraud scheme that involved mobile apps and content websites, as well as shell companies, fake employees and fake companies. I ultimately found more than 35 websites connected to the scheme. One way I identified many of the sites was by copying the text on one site’s About page and pasting it into the Google search box. I instantly found roughly 20 sites with the exact same text:

The fraudsters running the scheme also created websites for their front companies to help them appear legitimate when potential partners at ad networks visited to perform due diligence. One example was a company called Atoses. Its homepage listed several employees with headshots. Yandex’s reverse image search (the best image search for faces) quickly revealed that several of them were stock images:

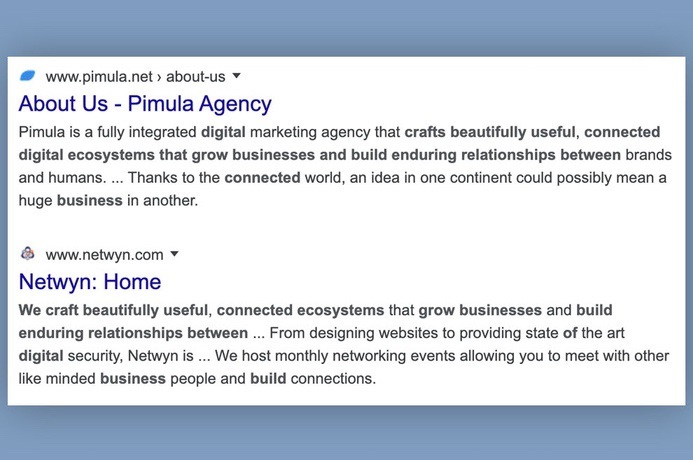

Atoses also had this text in the footer of its site: “We craft beautifully useful, connected ecosystems that grow businesses and build enduring relationships between online media and users.”

That same text appears on the sites of at least two marketing agencies:

If a company is using stock images for employees and plagiarized text on its site, you know it’s not what it claims to be.

It’s also a good idea to copy and paste text from articles on a site and enter them into Google or another search engine. Sometimes, a site that claims to be a source of news is just plagiarizing real outlets.

In 2019, I came across a site called forbesbusinessinsider.com that appeared to be a news site covering the tech industry. In reality it was mass plagiarizing articles from a wide variety of outlets, including, hilariously, an article I wrote about fake local websites.

Another basic step is to take the URL of a site and search it in Google. For example, “forbesbusinessinsider.com.” This will give you a sense of how many of the site’s pages have been indexed, and may also bring up examples of other people reporting on or otherwise talking about the site. You can also check if the site is listed in Google News by loading the main page of Google News and entering “forbesbusinessinsider.com” in the search box.

Another tip is to take the site URL and paste it into search bars at Twitter.com or Facebook.com. This will show you if people are linking to the site. During one investigation, I came across a site, dentondaily.com. Its homepage showed only a few articles from early 2020, but when I searched the domain on Twitter, I saw that it had previously pumped out plagiarized content, which had caused people to notice and complain. These older stories were deleted from the site, but the tweets provided evidence of its previous behavior.

Once you’ve dug into the content of a website, it’s time to understand how it spreads. We’ll look at two tools for this: BuzzSumo and CrowdTangle.

In 2016, I worked with researcher Lawrence Alexander to look at American political news sites being run from overseas. We soon zeroed in on sites run out of Veles, a town in North Macedonia. We used domain registration details (more on that below) to identify more than 100 U.S. political sites run from that town. I wanted to get a sense of how popular their content was, and what kind of stories they were publishing. I took the URLs of several sites that seemed to be the most active and created a search for them in BuzzSumo, a tool that can show a list of a website’s content ranked by how much engagement it received on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest and Reddit. (It has a free version, though the paid product offers far more results.)

I immediately saw that the articles from these sites with the most engagement on Facebook were completely false. This provided us with key information and an angle that was different from previous reporting. The below image shows the basic BuzzSumo search results screen, which lists the Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest and Reddit engagements for a specific site, as well as some sample false stories from 2016:

Another way to identify how a website’s content is spreading on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Reddit is to install the free CrowdTangle browser extension, or use its web-based link search tool. Both offer the same functionality, but let’s work with the web version. (These tools are free, but you need a Facebook account for access.)

The key difference between BuzzSumo and CrowdTangle is that you can enter the URL of a site in BuzzSumo and it will automatically bring up the most-engaged content on that site. CrowdTangle is used to check a specific URL on a site. So if you enter buzzfeednews.com, in CrowdTangle, it’s going to show you engagement stats only for that homepage, whereas BuzzSumo will scan across the entire domain for its top content. Another difference is that CrowdTangle’s link search tool and extension will show Twitter engagements only from the past seven days. BuzzSumo provides a count of all-time shares on Twitter for articles on the site.

As an example, I entered the URL of an old, false story about a boil water advisory in Toronto into CrowdTangle Link Search. (The site later deleted the story but the URL is still active as of this writing.) CrowdTangle shows that this URL received more than 20,000 reactions, comments and shares on Facebook since being published. It also shows some of the pages and public groups that shared the link, and offers the option to view similar data for Instagram, Reddit and Twitter. Remember: The Twitter tab will show tweets only from the past seven days.

Note that the high number of total Facebook interactions is not really reflected in the small list of pages and groups we see. This is at least partly because some of the key pages that spread the link when it was first published were later removed by Facebook. This is a useful reminder that CrowdTangle shows data only from active accounts, and it won’t show you every public account that shared a given URL. It’s a selection, but is still incredibly useful because it often reveals a clear connection between specific social media accounts and a website. If the same Facebook page is consistently — or exclusively — sharing content from a site, that may signal they’re run by the same people. Now you can dig into the page to compare information with the site and potentially identify the people involved and their motivations. Some of the Facebook link share results listed in CrowdTangle may also be of people sharing the article in a Facebook group. Note the account that shared the link, and see if they’ve spread other content from the site. Again, there could be a connection.

Registration

Every domain name on the web is part of a central database that stores basic information about its creation and history. In some cases, we also get lucky and find information about the person or entity that paid to register a domain. We can pull up this information with a whois search, which is offered by many free tools. There are also a handful of great free and low-priced tools that can bring up additional information, such as who has owned a domain over time, the servers it’s been hosted on, and other useful details.

One caveat is that it’s relatively inexpensive to pay to have your personal information privacy protected when you register a domain. If you do a whois search on a domain and the result lists something such as “Registration Private,” “WhoisGuard Protected,” or “Perfect Privacy LLC” as the registrant, that means it’s privacy protected. Even in those cases, a whois search will still tell us the date the domain was most recently registered, when it will expire and the IP address on the internet where the site is hosted.

DomainBigData is one of the best free tools for investigating a domain name and its history. You can also enter in an email or person or company name to search by that data instead of a URL. Other affordable services you may want to bookmark are DNSlytics, Security Trails and Whoisology. A great but more expensive option is the Iris investigations product from DomainTools.

For example, if we enter dentondaily.com into DomainBigData, we can see it’s been privacy protected. It lists the registrant name as “Whoisguard Protected.” Fortunately, we can still see that it was most recently registered in August 2019.

For another example, let’s search newsweek.com in DomainBigData. We immediately see that the owner has not paid for privacy protection. There’s the name of a company, an email address, phone and fax numbers.

We also see that this entity has owned the domain since May 1994, and that the site is currently hosted at the IP address 52.201.10.13. The next thing to note is that the name of the company, the email and the IP address are each highlighted as links. That means they could lead us to other domains that belong to Newsweek LLC, [email protected] and other websites hosted at that same IP address. These connections are incredibly important in an investigation, so it’s always important to look at other domains owned by the same person or entity.

As for IP addresses, beware that completely unconnected websites can be hosted on the same server. This is usually because people are using the same hosting company for their websites. A general rule is that the fewer the websites hosted on the same server, the more likely they may be connected. But it’s not for sure.

If you see hundreds of sites hosted on a server, they may have no ownership connection. But if you see there are only nine, for example, and the one you’re interested in has private registration information, it’s worth running a whois search on the eight other domains to see if they might have a common owner, and if it’s possible that person also owns the site you’re investigating. People may pay for privacy protection on some web domains but neglect to do it for others.

Connecting sites using IP, content and/or registration information is a fundamental way to identify networks and the actors behind them.

Now let’s look at another way to link sites using the code of a webpage.

Code and analytics

This approach, first discovered by Lawrence Alexander, begins with viewing the source code of a webpage and then searching within it to see if you can locate a Google Analytics and/or Google AdSense code. These are hugely popular products from Google that, respectively, enable a site owner to track the stats of a website or earn money from ads. Once integrated into a site, every webpage will have a unique ID linked to the owner’s Analytics or AdSense account. If someone is running multiple sites, they often use the same Analytics or AdSense account to manage them. This provides an investigator with the opportunity to connect seemingly separate sites by finding the same ID in the source code. Fortunately, it’s easy to do.

First, go to your target website. Let’s use dentondaily.com. In Chrome for Mac, select the “View” menu then “Developer” and “View Source.” This opens a new tab with the page’s source code. (On Chrome for PC, press ctrl-U.)

All Google Analytics IDs begin with “ua-” and then have a string of numbers. AdSense IDs have “pub-” and a string of numbers. You can locate then in the source code by simply doing a “find” on the page. On a Mac, type command-F; on a PC it’s ctrl-F. This brings up a small search box. Enter “ua-” or “pub-” and then you’ll see any IDs within the page.

If you find an ID, copy it and paste it into the search box in services such as SpyOnWeb, DNSlytics, NerdyData or AnalyzeID. Note that you often receive different results from each service, so it’s important to test an ID and compare the results. In the below image, you can see SpyOnWeb found three domains with the same AdSense ID, but DNSlytics and AnalyzeID found several more.

Sometimes a site had an ID in the past but it’s no longer present. That’s why it’s essential to use the same view source approach on any other sites that allegedly have these IDs listed to confirm they’re present. Note that AdSense and Analytics IDs are still present in the archived version of a site in the Wayback Machine. So if you don’t find an ID on a live site, be sure to check the Wayback Machine.

All of these services deliver some results for free. But it’s often necessary to pay to receive the full results, particularly if your ID is present on a high number of other sites.

A final note on inspecting source code: It’s worth scanning the full page even if you don’t understand HTML, JavaScript, PHP or other common web programming languages. For example, people sometimes forget to change the title of a page or website if they reuse the same design template. This simple error can offer a point of connection.

While investigating the ad fraud scheme with front companies like Atoses, I was interested in a company called FLY Apps. I looked at the source code of its one-page website and near the top of the site’s code I saw the word “Loocrum” in plain text (emphasis added):

Googling that word brought up a company called Loocrum that used the exact same website design as FLY Apps, and had some of the same content. A whois search revealed that the email address used to register loocrum.com had also been used to register other shell companies I previously identified in the scheme. This connection between FLY Apps and Loocrum provided important additional evidence that the four men running FLY Apps were linked to this overall scheme. And it was revealed by simply scrolling through the source code looking for plain text words that seemed out of place.

Conclusion

Even with all of the above approaches and tools under your belt, you might sometimes feel as though you’ve hit a dead end. But there’s often another way to find connections or avenues for further investigation on a website. Click every link, study the content, read the source code, see who’s credited the site, see who’s sharing it, and examine anything else you can think of to reveal what’s really going on.