2. Finding patient zero

Written by Henk van Ess

Henk van Ess is an assessor for Poynter’s International Fact-Checking Network. He is obsessed with finding stories in data. Van Ess trains worldwide media professionals in internet research, social media and multimedia. His clients include NBC News, BuzzFeed News, ITV, Global Witness, SRF, Axel Springer, SRF and numerous NGOs and universities. His websites whopostedwhat.com and graph.tips are heavily used to filter social media. He is @henkvaness on Twitter.

For decades, Canadian flight attendant Gaëtan Dugas was known as “Patient Zero,” the first man to bring AIDS to the United States. This distinction, which was reinforced by books, films and countless news reports made him the “arch-villain of an epidemic that would eventually kill more than 700,000 people in North America.”

But that was not the case. Bill Darrow, an investigator with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, interviewed Dugas and filed him as “Patient O, as in “Out-of-California.” It was soon misread as the number 0, setting off a chain reaction of misinformation that persisted until recently.

It’s also possible for a journalist to focus on the wrong patient 0 if you don’t know how to search properly. This chapter helps you to find primary sources online by getting rid of superficial results and digging deeper.

1. Risks of consulting primary sources and how to fix them

Journalists love online primary sources. Firsthand evidence can be found in a newspaper article, a scientific study, a press release, social media or any other possible “patient zero.”

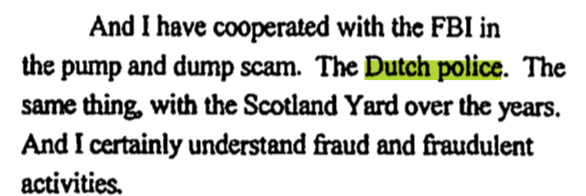

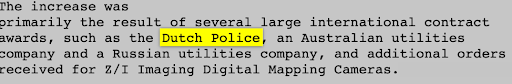

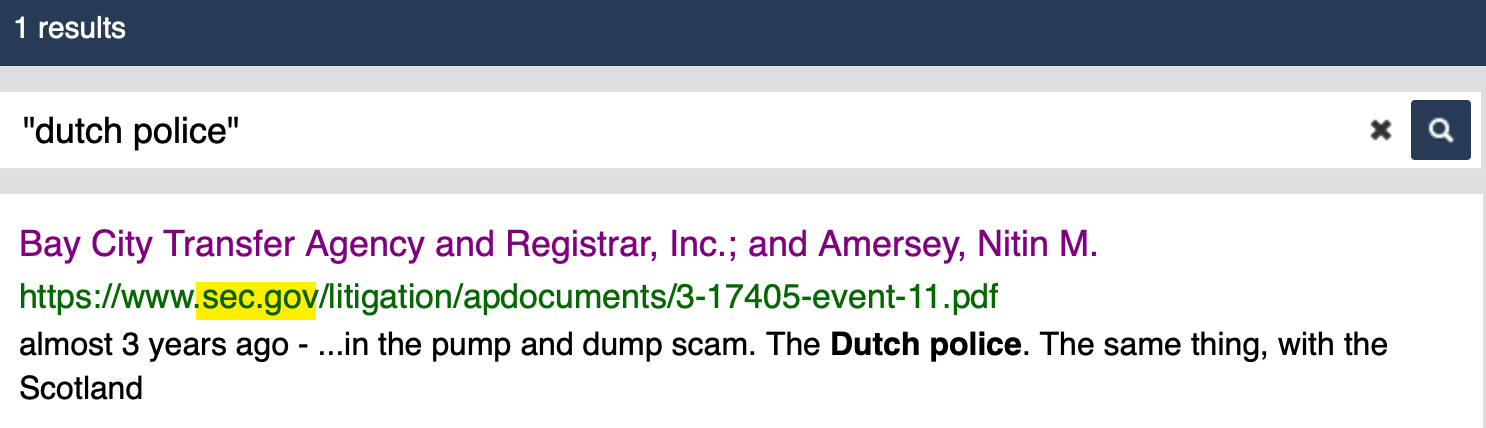

Performing a basic keyword search on an official government site can make you think “what you see is what they got.” That is often not true. Here is an example. Let’s go to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, a source used to find financial information about U.S. citizens as well as businesspeople from all over the world. Let’s say we want to find the first occurrence of the phrase “Dutch police” in sec.gov. The built-in search engine of the SEC can help:

You get just one hit — a document from 2016. So the SEC mentions the Dutch police only once, in 2016, right?

Wrong. The first mention on sec.gov was in 2004, 12 years earlier, in a declassified, encrypted mail:

You won’t see this in the search results from the search bar on sec.gov, even though this information does come straight from its website. Why the difference?

By default, you should distrust search engines from primary sources. They can give you a false impression of the actual content of the website and its associated databases. The proper way to search is to perform a “primary source check.”

Primary source check

Step 1: Look at the failing link

The search result from the SEC provided us with just one source:

Let’s work with that disappointment. First, get rid of “https://www,” the first part of the link. Watch out for the first backslash after that (/) — in this case it’s before the word “litigation/”

That’s the part we need: sec.gov

2. Second step: Use “site:”

Go to a generic search engine. Start with the query (“Dutch police”) and end with “site:” followed directly with the URL (no spaces). This is the formula for finding out if an original source shows you everything:

Including specific folders

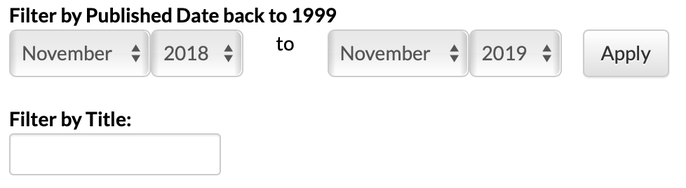

You can now adapt the “primary source formula” to your needs. Let’s go to the press release section of the New Jersey Courts website. Say you want to find out when the Mercer County Bar Association sponsored a Law Day program, but you can’t find the primary source in the title of any press release. The “Mercer County Bar Association” is not visible in any title.

Now look at the URL of that page full of poorly indexed press releases:

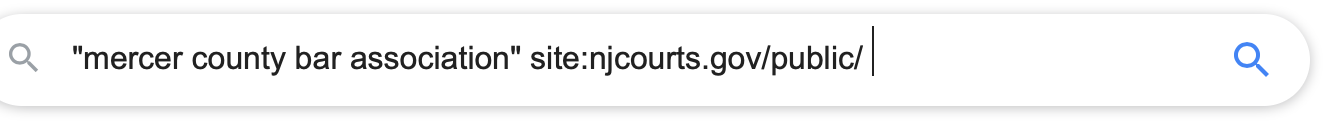

The public relations material is filed away in the folder /public. That should be included in your Google search:

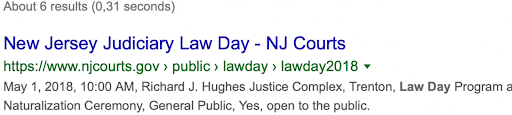

And there you are:

Predicting folders

China has a Ministry of Ecology and Environment. Do they have English documents about the German company Siemens? With the following formula, you get Chinese and English documents in the search results:

If you want to filter to see only the English ones, maybe they used the word English in the link? Try it out. It works:

2. Following the trail of documents

Sometimes the information we need isn’t contained on a webpage, but is actually in a document hosted on a website. Here’s how to follow the document trail using Google formulas.

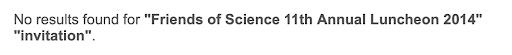

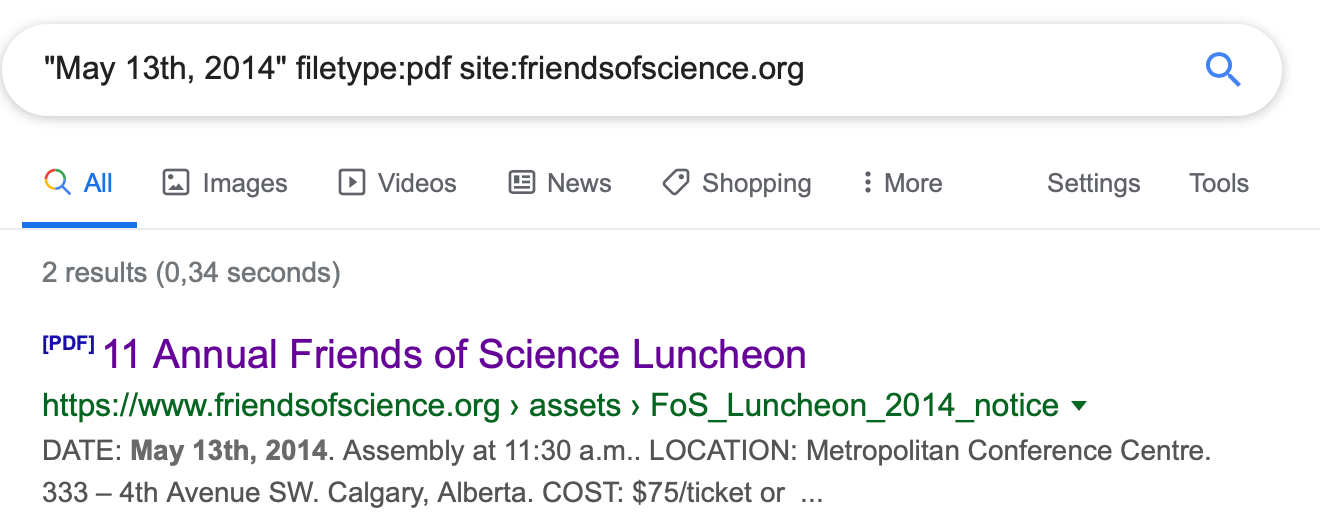

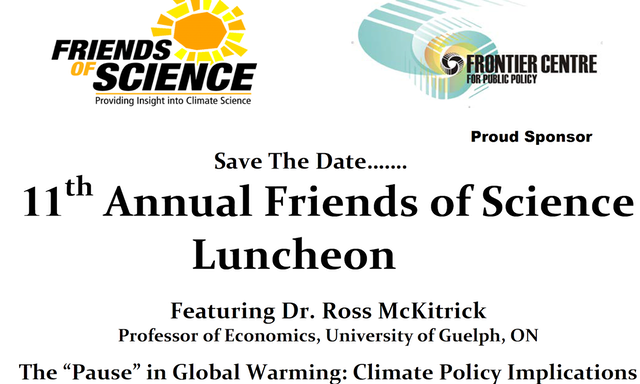

Ross McKitrick is an associate professor in the Economics Department at the University of Guelph, Ontario. Back in 2014, he did a presentation for a climate skeptic group. Let’s try to find the invitation for that meeting. We know it was held on May 13, 2014, and was the 11th Annual Luncheon organized by the “Friends of Science (FOS).” If we search Google for these terms we come up empty:

Why? Because the word invitation is not in many invitations. It’s the same with the word interview. Many interviews don’t contain the word interview. Even most maps don’t have the word map explicitly written on it. My advice? Stop guessing and Go Zen.

Step 1: Establish the document type

Try to find the common denominator of any online invitation. It's often a PDF document. Search for just that with “filetype:pdf” and you might find it.

Step 2: Be (climate) neutral

You don’t know the exact wording of the invitation. But what you do know, is that the YouTube video was from a May 13, 2014, event. It’s feasible that the date is mentioned in the invitation. (Be sure to search for both the cardinal and ordinal forms, May 13 and May 13th.)

Step 3: Who is involved?

We know the organizer is “Friends of Science” and its website is friendsofscience.org.

When you combine all three steps, the query in Google will be:

There it is in the first hit: the invitation for the event.

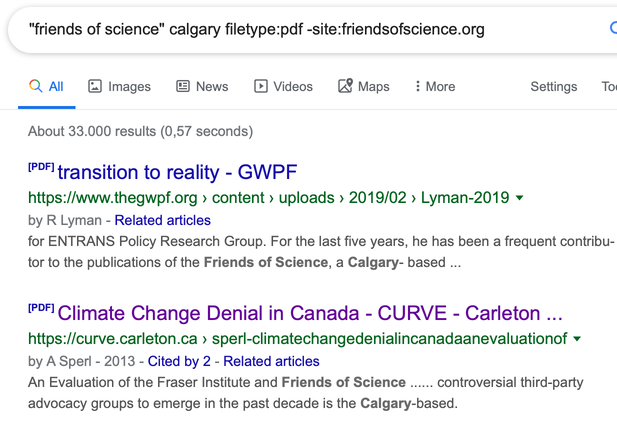

The FOS, based in Calgary, is frequently labeled a climate denial group and is funded in part by the oil and gas sector So how would we craft a query to find out more information about it and its network of supporters and funders?

Step 1: Include target

“Friends of Science” results in too many hits, so include also “Calgary.”

Step 2: Include “filetype”

Go for the next best thing for any official document, “filetype:pdf.”

Step 3: Exclude your target’s website

Exclude the target’s website Friendsofscience.org by adding “-site:friendsofscience.org.” This helps you find information from outside parties.

The full query is:

Because you searched for the target in official documents, but not from its own website, you find some brothers in arms and those who are critical of the organization:

3. Filtering social media for primary sources

YouTube

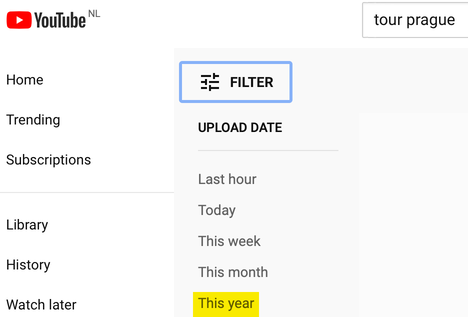

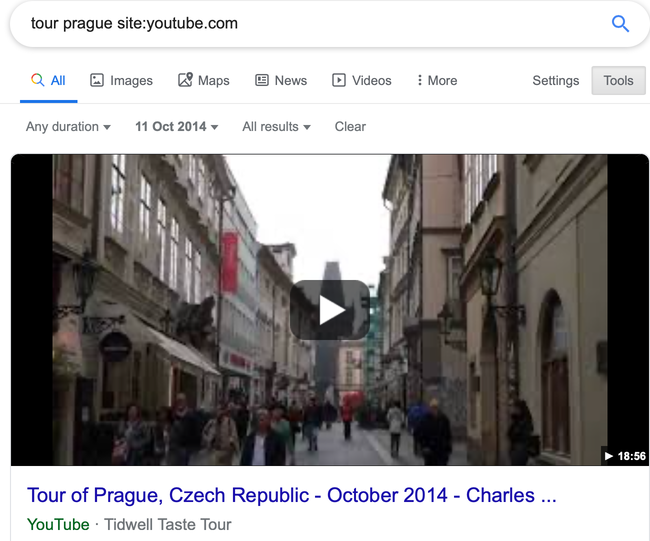

YouTube’s search tool has a problem: it won’t let you filter for videos that are older than one year. If you want to find a video of a tour in Prague from Oct 11, 2014, this is the roadblock you will hit:

To solve this, manually enter the preferred date into a Google.com search by using the “Tools” menu on the far right. Then select “Any time” and “Custom Range.” Now we get the results we need:

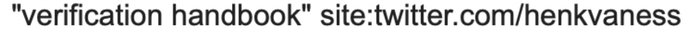

Despite the power of the “site:” search operator, you’ll be disappointed if you use it in Google to try searching Twitter. For example, we could try this query to find when I tweeted about the Verification Handbook for the first time:

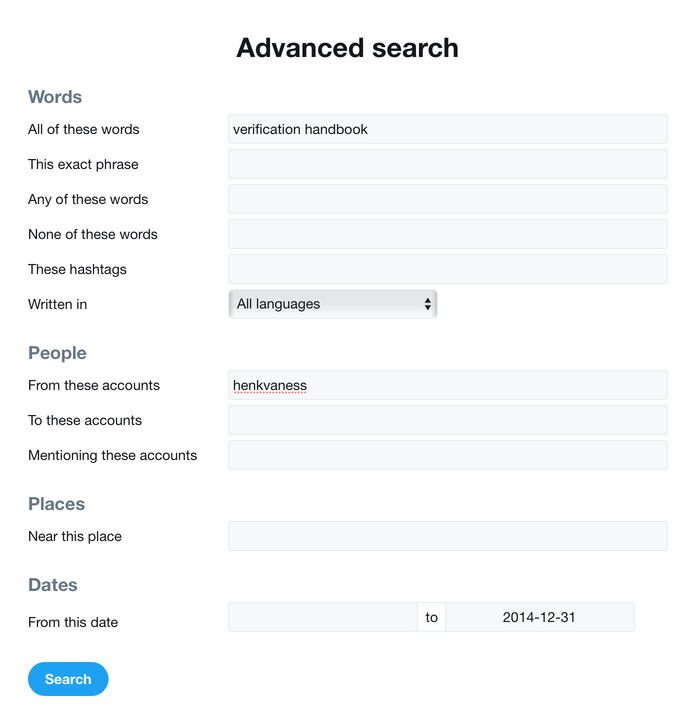

But it returns you only one hit as of this writing. Generic search engines like Google often struggle to deliver quality results from the trillions of posts on Twitter, or on big platforms such as Facebook and Instagram. The answer for Twitter is to use its Advanced Search functionality and add keywords, username and time period, as shown here:

Don't forget to click on “Latest" on the menu at the top of the search results page so you can view the results in reverse chronological order. By default, Twitter sorts your results by what it considers to be the top tweets.

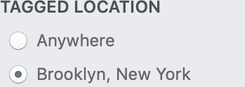

Using “site:” on Facebook is also not ideal, but we can make its native search tool fit our needs. Let’s say for example you want to see posts from March 2019 about strawberry cake from people in Brooklyn. Follow these steps:

Step 1: Type in query

Step 2: Click on posts

Step 3: Define location

Step 4: Choose a date

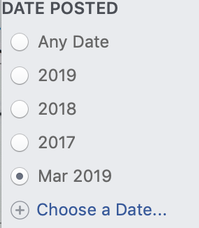

And there you are:

Instagram

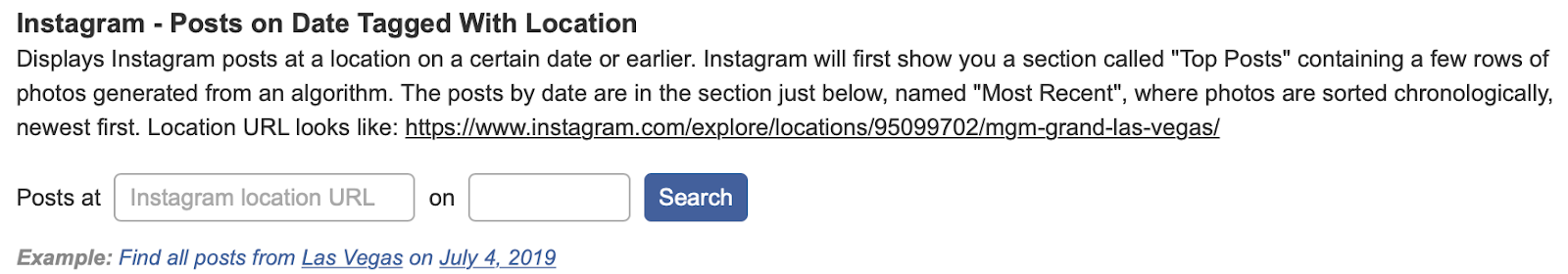

To search Instagram for posts from a specific date in a specific location, you can go to my site, whopostedwhat.com, and fill in your query: