1. Investigating Social Media Accounts

Written by: Brandy Zadrozny

Brandy Zadrozny is an investigative reporter for NBC News, where she mostly covers misinformation, disinformation and extremism on the internet.

Nearly every story I report involves social media sleuthing. From profile backgrounding to breaking news to longer investigations, social media platforms offer some of the best ways to learn about a subject’s real life — their family, friends, jobs, personal politics and associations — as well as a window into secret thoughts and hidden online identities.

It’s an incredible time to be a journalist; people increasingly live their lives online and tools to find and search a subject’s social profiles are ubiquitous. At the same time, both normal folks and bad actors are getting smarter about hiding their tracks. Meanwhile, social media platforms like Facebook have reacted to negative press about privacy breaches and harmful ideologies spread on their platform by closing down the tools that journalists and researchers have become reliant on to uncover stories and identify people.

In the following chapter I’ll show some core approaches for investigating social accounts. The tools are the ones currently in my rotation, but before long they’ll be killed by Facebook or replaced by something better. The reporters who are best at this work have their own processes and gadgets to get there, but really, as in any brand of reporting, obsession and (virtual) shoe leather yield the best results. Be prepared to read thousands of tweets, click until the end of the Google results, and dive down a social media rabbit hole if you want to collect the tiny biographical clues that will help you answer the question, “Who is this?”

Usernames

A username is sometimes all we have, which is fine, because it’s almost always where we start. Such was the case of a then-New Hampshire Republican state representative who built one of Reddit’s most popular and odious men’s communities. The investigation behind the unmasking of the architect of Reddit’s The Red Pill, now a quarantined community, started with the username “pk_atheist.”

Some people hold on to usernames, using them with minimal variations, across various platforms and email providers. The more security-focused, like the New Hampshire state representative, create and ditch usernames with each new endeavor.

Whatever the case, there are a few sites that you should feed the username you’re searching into.

First, I plug the username into Google. People — especially younger ones who eschew the larger social platforms — tend to leave a trail even in more unexpected places, including comment sections, reviews and forums, that can lead you to information and other accounts.

Along with a Google search, use proprietary services. They cost money and depending on your newsroom’s budget, you may or may not have access. Most shops have Nexis, which is great for public records and court documents but sadly lacking in the email/username department. It’s also useful for researching people only in the United States. Pipl and Skopenow are among the best tools I’ve found for cross referencing “real world” information like phone numbers and property records with online records like emails and usernames, and both work globally. These paid search engines often provide phone and property records, but they can also identify Facebook and LinkedIn profiles that remain even after an account has been closed. They also connect accounts that people have largely forgotten about, such as old blogs and even Amazon wish lists — a gold mine for learning about what a person reads, buys and wants. You also get a lot of false positives with these, so I tend to start my investigation with their results and continue with other means of verification.

When I find a username or email I think might belong to my subject, I plug it into an online tool like namechk or namecheckr that looks for username availability across multiple platforms. These tools are designed to be an easy way for marketers to see if a given username they’re planning to register is available across platforms. But they’re also useful for checking whether a username you’re investigating also exists elsewhere. Obviously, just because a username has been registered on multiple platforms doesn’t mean these accounts all belong to the same person. But it’s a great starting point to looking across platforms.

For further username checking, there’s haveibeenpwned.com and Dehashed.com, which search data breaches for user information and can be a quick way to validate an email address and provide new leads.

Photos

A username isn’t always enough to go on, and nothing persuades like a picture. Profile photos are another way to verify the identity of a person across different accounts.

Google’s reverse image search is fine, but often other search engines — especially Russia’s Yandex — may deliver better results. I use the Reveye Chrome extension, which allows me to right click on an image and search for its match across multiple platforms including Google, Bing, Yandex and Tineye. The Search by Image extension also has a neat capture function that allows you to search from an image within an image.

There are problems with reverse image searching, of course. The search engines referenced above do a poor job finding images across Twitter and are all but useless for turning up results from sites like Instagram and Facebook.

What I’m most often looking at are different images of people. I can’t count how many times I’ve squinted at my monitor and asked my colleagues, “Is this the same person?”

I just don’t trust my eyes. Identifying characteristics across photos like moles or facial hair or features is helpful; lately, I also like to check it with a facial recognition tool like Face++, which allows you to upload two photos and then gives a probability that those belong to the same person. In these examples, the tool was able to positively identify me in photos 10 years apart. It also identified my colleague Ben across social media profile pics on Twitter and Facebook while correctly noting that he is not, in fact, Ben Stiller.

If you’re chasing trolls or scammers, you might find they’ve put more effort into obscuring their profile photo, or they may use fake photos. That’s when editing the photo and flipping it might help reverse engineer their process.

It’s not just profile photos that can be signposts, however. As people become more aware of and concerned with their own privacy and that of their family, they’re still inclined to share photos of things they’re proud of. I’ve identified people by connecting photos of things like cars, homes or pets. In this sense, photos become a means to connect accounts and the people behind them to one another, enabling you to build out the network around your target. This is a core practice when investigating social media accounts.

For example, we were looking to confirm the social accounts of a man who shot and killed nine people outside of a bar in Dayton, Ohio. His Twitter account offered clues to his political ideology but his handle, @iamthespookster, was unique and didn’t resemble his real name, which had been released by authorities. The fact that one of his victims was his sibling, a transgender man whose name was not in public records and hadn’t come out to the wider world yet, further complicated identifying the key figures. But throughout his and his family’s profiles were pictures of a dog, a pet that appeared as the banner image of his transgender brother’s unreported account.

The dog wasn’t the only helpful detail in the previous image. That image came from the Ohio shooter’s father, and helped us verify his personal accounts and those belonging to his family.

If you have an account on Facebook or Twitter, I can probably tell you the day you were born, even if you don’t share it on your profile or post about it yourself. Since a date of birth is often one of the first identifying pieces of police-provided information in breaking news situations, a reliable way to verify a social media account is by scrolling to the month and day in question on a suspected account and looking out for birthday wishes. Even if their own pages are empty, often moms and dads (like Connor Betts’ above) will post about their children’s birthdays.

The same is true for Twitter, because who doesn’t love a birthday?

But it’s even easier to find an identifying post on Twitter, because its advanced search tool is among the best offered by social platforms. Although I rarely announce my birthday, if ever, I was able to find a birthday tweet from a loving colleague who outed me.

Birthdays are just one example. Weddings, funerals, holidays, anniversaries, graduations — nearly every major life marker is celebrated on social media. These provide an opening for searching and investigating an account.

You can search for these keywords and by other filters with Facebook search tools. They don’t get as much mileage as they did before the platform’s pivot to privacy, but they exist. One of my favorites is whopostedwhat.com.

Relationships

You can judge a person by the company they keep on social media. We can tell a lot about a person’s life and leanings by examining the people with whom they interact online.

When I first joined Twitter, I made my husband and best friend sign up too, just so they could follow me. I think about that when I’m looking into accounts for work. The platforms don’t want you to be alone, either, so when you first open an account, an algorithm powers up. Influenced by the contacts list in your phone, your appearance in the contact lists of existing accounts, your location and other factors, a platform will suggest accounts to follow.

Because of that truth, it’s always illuminating to look at an account’s earliest followers and friends. TweetBeaver is a good tool for investigating the connections between large accounts and for downloading things like timelines and favorites of smaller accounts. For larger datasets, I rely on a developer with API access.

Let’s take The Columbia Bugle, a popular far-right anonymous Twitter account that boasts that it was retweeted twice by Donald Trump’s account.

The earliest follows of Max Delarge, an account claiming to be the editor of The Columbia Bugle, are San Diego-specific news sources and San Diego-specific sports accounts. Since many of Columbia Bugle’s tweets include videos from San Diego Trump rallies and events at the University of California, San Diego, we can be fairly confident that the person behind the account lives near San Diego.

With a new investigation, I like to start at the beginning of someone’s Twitter history and work forward in time. You can get there by hand, with an assist from an autoscroller chrome extension, or you can use Twitter’s advanced search to limit the time frame to the first few months of an account’s existence.

Curiously, the first six months of this account shows zero tweets.

This suggests that the person behind The Columbia Bugle might have deleted his earlier tweets. To find out why that might be, I can tweak my search. Instead of tweets from the account I’ll look for any tweets mentioning The Columbia Bugle.

These conversations confirm that ColumbiaBugle erased its first year of tweets, but doesn’t tell us why and the first accounts that the account interacted with don’t offer many clues.

To find recently deleted tweets, you can search Google’s cache; older deleted tweets can also sometimes be accessed in the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine or another archive. The manual archive site archive.is turns up several deleted tweets from where ColumbiaBugle participated in an event where college students wrote pro-Trump messages on their campuses. To see all the tweets someone may have archived from that account, as I did to find this tweet, you can search by URL prefix, using an asterisk after the account name like this:

It’s rare for someone to successfully keep their real life separate from their online activities. For example, my NBC News colleague and I told the story of 2016’s most viral — and misleading — Election Day voter fraud claim, with an assist from a neighborhood acquaintance of the far-right troll who tweeted it.

Though the tweet originated with a man known to his followers as @lordaedonis, people from his actual neighborhood had responded to past tweets with his real name, which we included in a profile of an attention-hungry entrepreneur whose tweet was spread by a Kremlin-backed Twitter account, and eventually seen by millions and promoted by the soon-to-be president.

My favorite kind of stories are those that reveal the real people behind influential, anonymous social media accounts. These secret accounts are less reliant on the algorithm, and more carefully crafted to be an escape from public life. They allow someone to keep tabs on and communicate with family and friends apart from their public account, or to communicate the ideas and opinions that for personal or political reasons, they dare not say out loud.

Journalist Ashley Feinberg is the fairy godmother of these kind of juicy stories, ones that unmask the alt accounts of prominent figures like James Comey or Mitt Romney. Her secret was simply a matter of finding smaller accounts of family members that Comey and Romney would naturally want to follow, and then scrolling through them until she found an account that seemed inauthentic but whose content and friends/followers network matched that of these real people.

Be wary of fake accounts

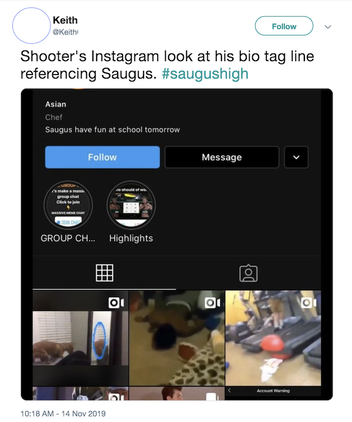

Each platform has its own personality, search capabilities and usefulness in different news situations. But a word of caution with social media accounts: The same rule of trust but verify applies. Groups of people revel in tricking journalists. Especially in breaking news situations, fake accounts will always be born, many with ominous or threatening posts meant to attract reporters. This fake Instagram account used the name of a mass shooter and was created after a shooting at Saugus High School in California. It gained attention via screenshots on Twitter, but BuzzFeed News later revealed it did not belong to the shooter.

Confirming a social account with the subject, family and friends, law enforcement and/or social media PR are ways to protect yourself from being duped.

Finally, and perhaps the most important note: There’s no one right order in which to complete these steps. Often, I’m led down rabbit holes and have more tabs open than I’m proud of. Creating a system that you can replicate — whether it’s tracking your steps in a Google doc or letting a paid tool like Hunchly monitor as you search — is the key to clarifying connections between people and the lives they lead online, and turning those conclusions into stories.