11. Network analysis and attribution

Written by: Ben Nimmo

Ben Nimmo is director of investigations at Graphika and a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab. He specializes in studying large-scale cross-platform information and influence operations. He spends his leisure time underwater, where he cannot be reached by phone.

When dealing with any suspected information operation, one key question for a researcher is how large the operation is and how far it spreads. This is separate from measuring an operation’s impact, which is also important: It’s all about finding the accounts and sites run by the operation itself.

For an investigator, the goal is to find as much of the operation as possible before reporting it, because once the operation is reported, the operators can be expected to hide — potentially by deleting or abandoning other assets.

The first link in the chain

In any investigation, the first clue is the hardest one to find. Often, an investigation will begin with a tipoff from a concerned user or (more rarely) a social media platform. The Digital Forensic Research Lab’s work to expose the suspected Russian intelligence operation “Secondary Infektion” began with a tipoff from Facebook, which had found 21 suspect accounts on its platform. The work culminated six months later when Graphika, Reuters and Reddit exposed the same operation’s attempt to interfere in the British election. An investigation into disinformation targeting U.S. veterans began with the discovery by a Vietnam Veterans of America employee that its group was being impersonated by a Facebook page with twice as many followers as their real presence on the platform.

There is no single rule for identifying the first link in the chain by your own resources. The most effective strategy is to look for the incongruous. It could be a Twitter account apparently based in Tennessee but registered to a Russian mobile phone number; it could be a Facebook page that claims to be based in Niger, but is managed from Senegal and Portugal. It could be a YouTube account with a million views that posts vast quantities of pro-Chinese content in 2019, but almost all its views came from episodes of British sitcoms that were uploaded in 2016.

It could be an anonymous website that focuses on American foreign policy, but is registered to the Finance Department of the Far Eastern Military District of the Russian Federation. It could be an alleged interview with an “MI6 agent” couched in stilted, almost Shakespearean English. It could even be a Twitter account that intersperses invitations to a pornography site with incomplete quotations from Jane Austen’s “Sense and Sensibility.”

The trick with all such signals is to take the time to think them through. Investigators and journalists are so often pressured for time that it is easy to dismiss signals by thinking “that’s just weird,” and moving on. Often, if something is weird, it is weird for a reason. Taking the time to say “That’s weird: Why is it like that?” can be the first step in exposing a new operation.

Assets, behavior, content

Once the initial asset — such as an account or website — is identified, the challenge is to work out where it leads. Three questions are crucial here, modeled on Camille François’ Disinformation ABC:

- What information about the initial asset is available?

- How did the asset behave?

- What content did it post?

The first step is to glean as much information as possible about the initial asset. If it is a website, when was it registered, and by whom? Does it have any identifiable features, such as a Google Analytics code or an AdSense number, a registration email address or phone number? These questions can be checked by reference to historical WhoIs records, provided by services such as lookup.icann.com, domaintools.com, domainbigdata. com or the unnervingly named spyonweb.com.

Web registration details for the website NBeneGroup.com, which claimed to be a “Youth Analysis Group,” showing its registration to the Finance Department of the Far Eastern Military District of the Russian Federation, from lookup.icann.org.

Website information can be used to search for more assets. Both domaintools.com and spyonweb.com allow users to search by indicators such as IP address and Google Analytics code, potentially leading to associated websites — although the savvier information operations now typically hide their registration behind commercial entities or privacy services, making this more difficult.

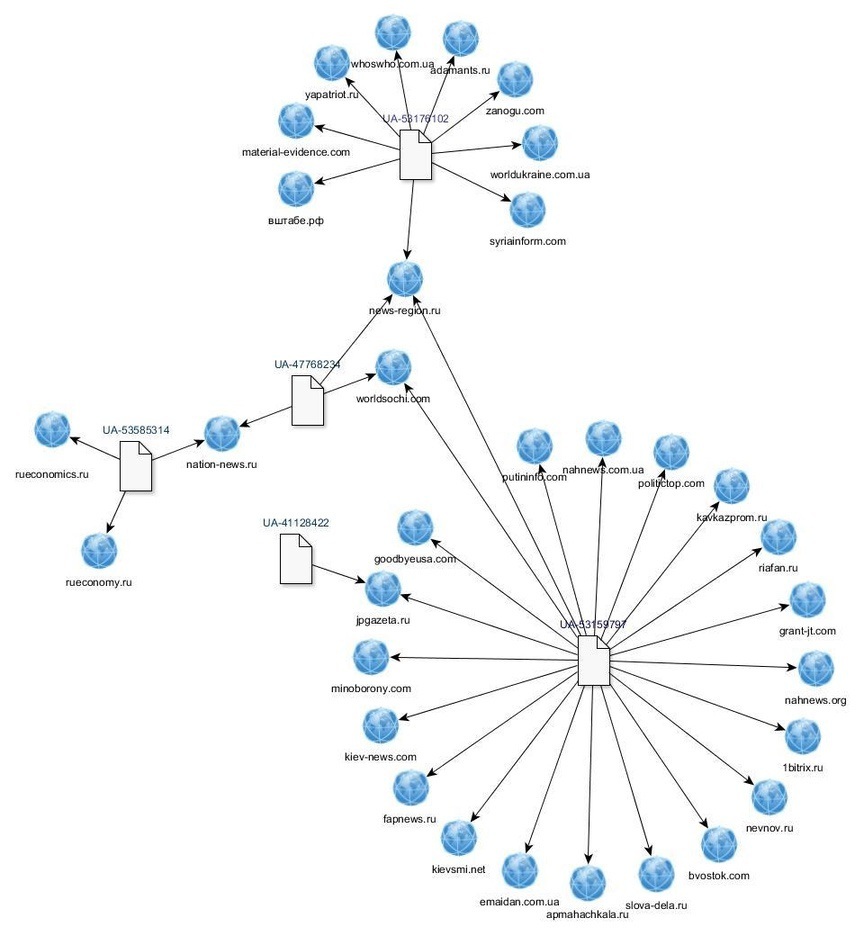

An early piece of analysis by British researcher Lawrence Alexander identified 19 websites run by the Russian Internet Research Agency by following their Google Analytics numbers. In August 2018, security firm FireEye exposed a large-scale Iranian influence operation by using registration information, including emails, to connect ostensibly unconnected websites.

Network of related websites connected by their Google Analytics codes (eight-digit numbers prefixed with the letters UA), identified by British researcher Lawrence Alexander

If the initial asset is a social media account, the guidance offered in the previous two chapters about bots and inauthentic activity, and investigating social accounts, applies. When was it created? Does its screen name match the name given in its handle? (If the handle is “@moniquegrieze” and the screen name is “Simmons Abigayle,” it’s possible the account was hijacked or part of a mass account creation effort.)

Three Twitter accounts involved in a major bot operation in August 2017. Compare the screen names with the handles, indicating that these were most probably accounts that had been hijacked, renamed and repurposed by the bot herder.

Does it provide any verifiable biographical detail, or links to other assets on the same or other platforms? If it’s a Facebook page or group, who manages it, and where are they located? Whom does it follow, and who follows it? Facebook’s “Page transparency” and “group members” settings can often provide valuable clues, as can Twitter profile features such as the date joined and the overall number of tweets and likes. (On Facebook and Instagram, it’s not possible to see the date the account was created, but the date of its first profile picture upload provides a reasonable proxy.)

Website and Facebook Page transparency for ostensible fact-checking site “C’est faux — Les fake news du Mali” (It’s false — fake news from Mali), showing that it claimed to be run by a student group in Mali, but was actually managed from Portugal and Senegal. Image from DFRLab.

Once the details of the asset have been recorded, the next step is to characterize its behavior. The test question here is, “What behavioral traits are most typical of this asset, and might be useful to identify other assets in the same operation?”

This is a wide-ranging question, and can have many answers, some of which may emerge only in the later stages of an investigation. It could include, for example, YouTube channels that have Western names and profile pictures, but post Chinese-language political videos interspersed with large quantities of short TikTok videos. It could include networks of Facebook or Twitter accounts that always share links to the same website, or the same collection of websites. It could include accounts that use the same wording, or close variations on the same wording, in their bios. It could include “journalist” personas that have no verifiable biographical details, or that give details which can be identified as false. It could include websites that plagiarize most of their content from other sites, and insert only the occasional partisan, polemic or deceptive article. It could include many such factors: The challenge for the researcher is to identify a combination of features that allows them to say, “This asset is part of this operation.”

Behavior patterns: An article originally posted to the website of Iran’s Ayatollah Khamenei, and then reproduced without attribution by IUVMpress.com and britishleft.com, two websites in an Iranian propaganda network. Image from DFRLab.

Sometimes, the lack of identifying features can itself be an identifying feature. This was the case with the “Secondary Infektion” campaign run from Russia. It used hundreds of accounts on different blogging platforms, all of which included minimal biographical detail, posted one article on the day they were created, and were then abandoned, never to be used again. This behavior pattern was so consistent across so many accounts that it became clear during the investigation that it was the operation’s signature. When anonymous accounts began circulating leaked US-UK trade documents just before the British general election of December 2019, Graphika and Reuters showed that they exactly matched that signature. Reddit confirmed the analysis.

Reddit profile for an account called “McDownes,” attributed by Reddit to Russian operation “Secondary Infektion.” The account was created on March 28, 2019, posted one article just over one minute after it was created, and then fell silent. Image from Graphika, data from redective.com.

Content clues can also help to identify assets that are part of the same network. If a known asset shares a photo or meme, it’s worth reverse-searching the image to see where else it has been used. The RevEye plug-in for web browsers is a particularly useful tool, as it allows investigators to reverse search via Google, Yandex, TinEye, Baidu and Bing. It’s always worth using multiple search engines, as they often provide different results.

If an asset shares a text, it’s worth searching where else that text appeared. Especially with longer texts, it’s advisable to select a sentence or two from the third or fourth paragraphs, or lower, as deceptive operations have been known to edit the headlines and ledes of articles they have copied, but are less likely to take the time to edit the body of the text. Inserting the chosen section in quotation marks in a Google search will return exact matches. The “tools” menu can also sort any results by date.

Results of a Google search for a phrase posted by a suspected Russian operation, showing the Google tools functionality to date-limit the search.

Assets that post text with mistakes have particular value, as errors are, by their nature, more unusual than correctly spelled words. For example, an article by a suspected Russian intelligence operation referred to Salisbury, the British city where former Russian agent Sergei Skripal was poisoned, as “Solsbury.” This made for a much more targeted Google search with far fewer results than a search for “Skripal” and “Salisbury.” It therefore produced a far higher proportion of significant finds.

With content clues, it’s especially important to look to other indicators, such as behavior patterns, to confirm whether an asset belongs to an operation. There are many legitimate reasons for unwitting users to share content from information operations. That means the sharing of content from an operation is a weak signal. For example, many users have shared memes from the Russian Internet Research Agency because those memes had genuine viral qualities. Simple content sharing is not enough on its own to mark out an operational asset.

Gathering the evidence

Information and influence operations are complex and fast moving. One of the more frustrating experiences for an open-source researcher is seeing a collection of assets taken offline halfway through an investigation. A key rule of analysis is therefore to record them when you find them, because you may not get a second chance.

Different researchers have different preferences for recording the assets they find, and the needs change from operation to operation. Spreadsheets are useful for recording basic information about large numbers of assets; shared cloud-based folders are useful for storing large numbers of screenshots. (If screenshots are required, it is vital to give the file an identifiable name immediately: few things are more annoying than trying to work out which of 100 files called “Screenshot” is the one you need.) Text documents are good for recording a mixture of information, but rapidly become cluttered and unwieldy if the operation is large.

Whatever the format, some pieces of information should always be recorded. These include how the asset was found (an essential point), its name and URL, the date it was created (if known), and the number of followers, follows, likes and/or views. They also include a basic description of the asset (for example, “Arabic-language pro-Saudi account with Emma Watson profile picture”), to remind you what it was after looking at 500 other assets. If working in a team, it is worth recording which team member looked at which asset.

Links can be preserved by using an archive service such as the Wayback Machine or archive.is, but take care that the archives do not expose genuine users who may have interacted unwittingly with suspect assets, and make sure that the archive link preserves visuals, or take a screenshot as backup. Make sure that all assets are stored in protected locations, such as password-protected files or encrypted vaults. Keep track of who has access, and review the access regularly.

Finally, it’s worth giving the asset a confidence score. Influence operations often find unwitting users to amplify their content: indeed, that is often the point. How sure are you that the latest asset is part of this operation, and why? The level of confidence (high, moderate or low) should be marked as a separate entry, and the reasons (discussed below) should be added to the notes.

Attribution and confidence

The greatest challenge in identifying an information operation lies in attributing it to a specific actor. In many cases, precise attribution will lie beyond the reach of open-source investigators. The best that can be achieved is a degree of confidence that an operation is probably run by a particular actor, or that various assets belong to a specific operation, but establishing who is behind the operation is seldom possible with open sources.

Information such as web registrations, IP addresses and phone numbers can provide a firm attribution, but they are often masked to all but the social media platforms. That’s why contacting the relevant platforms is a vital part of investigative work. As the platforms have scaled up their internal investigative teams, they've become more willing to offer public attribution for information operations. The firmest attribution in recent cases has come directly from the platforms, such as Twitter’s exposure of Chinese state-backed information operations targeting Hong Kong, and Facebook’s exposure of operations linked to the Saudi government.

Content clues can play a role. For example, an operation exposed on Instagram in October 2019 posted memes that were almost identical with memes posted by the Russian Internet Research Agency, but stripped out the IRA’s watermarks. The only way they could have made these memes was to source the original images that were the basis for the IRA’s posts and then rebuild the memes on top of them. Ironically, this attempt to mask the origins of the IRA posts suggested that the originators were, in fact, the IRA.

Similarly, a large network of apparently independent websites repeatedly posted articles that had been copied, without attribution, from Iranian government sources. This pattern was so repetitive that it turned out to be the websites’ main activity. As such, it was possible to attribute this operation to pro-Iranian actors, but it was not possible to further attribute it to the Iranian government itself.

Ultimately, attribution is a question of self-restraint. The researcher has to imagine the question, “How can you prove that this operation was run by the person you’re accusing?” If they cannot answer that question with confidence to themselves, they should steer clear of making the accusation. Identifying and exposing an information operation is difficult and important work, and reaching to make an unsupported or inaccurate attribution can undermine everything that came before it.