The Web as a Data Source

How can you find out more about something that only exists on the internet? Whether you’re looking at an email address, website, image, or Wikipedia article, in this chapter I’ll take you through the tools that will tell you more about their backgrounds.

Web Tools

First, a few different services you can use to discover more about an entire site, rather than a particular page.

- Whois

-

If you go to whois.domaintools.com (or just type whois www.example.com in Terminal.app on a Mac) you can get the basic registration information for any website. In recent years, some owners have chosen ‘private’ registration which hides their details from view, but in many cases you’ll see a name, address, email and phone number for the person who registered the site. You can also enter numerical IP addresses here and get data on the organization or individual that owns that server. This is especially handy when you’re trying to track down more information on an abusive or malicious user of a service, since most websites record an IP address for everyone who accesses them.

- Blekko

-

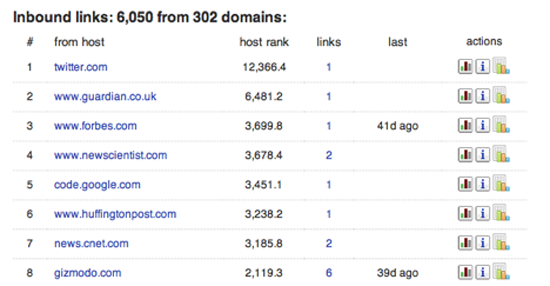

The Blekko search engine offers an unusual amount of insight into the internal statistics it gathers on sites as it crawls the web. If you type in a domain name followed by ‘/seo’ you’ll receive a page of information on that URL. The first tab in Figure 59 shows you which other sites are linking to the domain in popularity order. This can be extremely useful when you’re trying to understand what coverage a site is receiving, and if you want to understand why it’s ranking highly in Google’s search results, since they’re based on those inbound links. Figure 61 tells you which other websites are running from the same machine. It’s common for scammers and spammers to astroturf their way towards legitimacy by building multiple sites that review and link to each other. They look like independent domains, and may even have different registration details but often they’ll actually live on the same server because that’s a lot cheaper. These statistics give you an insight into the hidden business structure of the site you’re researching.

- Compete.com

-

By surveying a cross-section of American consumers, Compete.com builds up detailed usage statistics for most websites, and they make some basic details freely available. Choose the ‘Site Profile’ tab and enter a domain (Figure 62). You’ll then see a graph of the site’s traffic over the last year, together with figures for how many people visited, and how often (as in Figure 63). Since they’re based on surveys, the numbers are only approximate, but I’ve found them reasonably accurate when I’ve been able to compare them against internal analytics. In particular, they seem to be a good source when comparing two sites, since while the absolute numbers may be off for both, it’s still a good representation of their relative difference in popularity. They only survey US consumers though, so the data will be poor for predominantly international sites.

- Google’s Site Search

-

One feature that can be extremely useful when you’re trying to explore all the content on a particular domain is the ‘site:’ keyword. If you add ‘site:example.com’ to your search phrase, Google will only return results from the site you’ve specified. You can even narrow it down further by including the prefix of the pages you’re interested in, for example ‘site:example.com/pages/’, and you’ll only see results that match that pattern. This can be extremely useful when you’re trying to find information that domain owners may have made publicly available but aren’t keen to publicise, so picking the right keywords can uncover some very revealing material.

Web Pages, Images, and Videos

Sometimes you’re interested in the activity that’s surrounding a particular story, rather than an entire website. The tools below give you different angles on how people are reading, responding to, copying, and sharing content on the web.

- Bit.ly

-

I always turn to bit.ly when I want to know how people are sharing a particular link with each other. To use it, enter the URL you’re interested in. Then click on the ‘Info Page+’ link. That takes you to the full statistics page (though you may need to choose ‘aggregrate bit.ly link’ first if you’re signed in to the service). This will give you an idea of how popular the page is, including activity on Facebook and Twitter, and below that you’ll see public conversations about the link provided by backtype.com. I find this combination of traffic data and conversations very helpful when I’m trying to understand why a site or page is popular, and who exactly its fans are. For example, it provided me with strong evidence that the prevailing narrative about grassroots sharing and Sara Palin was wrong.

-

As the micro-blogging service becomes more widely used, it becomes more useful as a gauge of how people are sharing and talking about individual pieces of content. It’s deceptively simple to discover public conversations about a link. You just paste the URL you’re interested in into the search box, and then possibly hit ‘more tweets’ to see the full set of results.

- Google’s Cache

-

When a page becomes controversial, the publishers may take it down or alter it without acknowledgement. If you suspect you’re running into the problem, the first place to turn is Google’s cache of the page as it was when it did its last crawl. The frequency of crawls is constantly increasing, so you’ll have the most luck if you try this within a few hours of the suspected changes. Enter the target URL in Google’s search box, and then click the triple arrow on the right of the result for that page. A graphical preview should appear, and if you’re lucky there will be a small ‘Cache’ link at the top of it. Click that to see Google’s snapshot of the page. If that has trouble loading, you can switch over to the more primitive text-only page by clicking another link at the top of the full cache page. You’ll want to take a screenshot or copy-paste any relevant content you do find, since it may be invalidated at any time by a subsequent crawl.

- The Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine

-

If you need to know how a particular page has changed over a longer time period, like months or years, the Internet Archive runs a service called The Wayback Machine that periodically takes snapshots of the most popular pages on the web. You go to the site, enter the link you want to research, and if it has any copies it will show you a calendar so you can pick the time you’d like to examine. It will then present a version of the page roughly as it was at that point. It will often be missing styling or images, but it’s usually enough to understand what the focus of that page’s content was then.

- View Source

-

It’s a bit of a long-shot, but developers often leave comments or other clues in the HTML code that underlies any page. It will be on different menus depending on your browser, but there’s always a ‘View source’ option that will let you browse the raw HTML. You don’t need to understand what the machine-readable parts mean, just keep an eye out for the pieces of text that are often scattered amongst them. Even if they’re just copyright notices or mentions of the author’s names, these can often give important clues about the creation and purpose of the page.

- TinEye

-

Sometimes you really want to know the source of an image, but without clear attribution text there’s no obvious way to do this with traditional search engines like Google. TinEye offers a specialised ‘reverse image search’ process, where you give it the image you have, and it finds other pictures on the web that look very similar. Because they use image recognition to do the matching, it even works when a copy has been cropped, distorted or compressed. This can be extremely effective when you suspect that an image that’s being passed off as original or new is being misrepresented, since it can lead back to the actual source.

- YouTube

-

If you click on the ‘Statistics’ icon to the lower right of any video, you can get a rich set of information about its audience over time. While it’s not complete, it is useful for understanding roughly who the viewers are, where they are coming from, and when.

- Emails

-

If you have some emails that you’re researching, you’ll often want to know more details about the sender’s identity and location. There isn’t a good off-the-shelf tool available to help with this, but it can be very helpful to know the basics about the hidden headers included in every email message. These work like postmarks, and can reveal a surprising amount about the sender. In particular, they often include the IP address of the machine that the email was sent from, a lot like caller ID on a phone call. You can then run whois on that IP number to find out which organization owns that machine. If it turns out to be someone like Comcast or AT&T who provide connections to consumers, then you can visit MaxMind to get its approximate location. To view these headers in Gmail, open the message and open the menu next to reply on the top right and choose ‘Show original’. You’ll then see a new page revealing the hidden content. There will be a couple of dozen lines at the start that are words followed by a colon. The IP address you’re after may be in one of these, but its name will depend on how the email was sent. If it was from Hotmail, it will be called ‘X-Originating-IP:’, but if it’s from Outlook or Yahoo it will be in the first line starting with ‘Received:’. Running the address through Whois tells me it’s assigned to Virgin Media, an ISP in the UK, so I put it through MaxMind’s geolocation service to discover it’s coming from my home town of Cambridge. That means I can be reasonably confident this is actually my parents emailing me, not impostors!

Trends

If you’re digging into a broad topic rather than a particular site or item, here’s a couple of tools that can give you some insight.

- Wikipedia Article Traffic

-

If you’re interested in knowing how public interest in a topic or person has varied over time, you can actually get day-by-day viewing figures for any page on Wikipedia at stats.grok.se/. This site is a bit rough and ready, but will let you uncover the information you need with a bit of digging. Enter the name you’re interested in to get a monthly view of the traffic on that page. That will bring up a graph showing how many times the page was viewed for each day in the month you specify. Unfortunately you can only see one month at a time, so you’ll have to select a new month and search again to see longer-term changes.

- Google Insights

-

You can get a clear view into the public’s search habits using Insights from Google. Enter a couple of common search phrases, like ‘Justin Bieber vs Lady Gaga’, and you’ll see a graph of their relative number of searches over time. There’s a lot of options for refining your view of the data, from narrower geographic areas, to more detail over time. The only disappointment is the lack of absolute values, you only get relative percentages which can be hard to interpret.