Our next Conversations with Data podcast will take place on Thursday 10 June at 4 pm CEST / 7 am PT with Ben Jones, founder of Data Literacy, an organisation aiming to help you learn the language of data. During our live Q&A, he will reveal his top tips and tricks for becoming an effective data storyteller. The conversation will be our first live event on our Discord Server. Share your questions with us live and be part of our Conversations with Data podcast. Add to your calendar now.

Every news story has a data angle to it. Journalists may find themselves exploring questions such as:

- What percent of citizens polled favour proposed legislation?

- What was the safety rating of a bridge that has recently been closed for repairs, how many commuters will be affected, and for how long?

- How deadly was a recent hurricane, how strong were its winds when it made landfall, and what was the estimated price tag of the damage it caused?

The answers to these questions can be communicated to readers in the form of numbers, tables, charts, and maps. Journalists have been doing this for centuries, as ProPublica’s Scott Klein detailed brilliantly in his 2016 Tapestry Conference keynote titled “The Forgotten History of Visualization in the News.”

Of course, we shouldn’t get carried away with ourselves: the data angle isn’t the only angle. Every story also has a human angle to it – often multiple human angles, in fact. The human angles are the real story; the data angle supports them, gives them context, and adds perspective. These two types of angles are complementary. Together, they can make up the full arc of a rich story that affects both the hearts and minds of the reader.

Some stories that we encounter about our world have more pivotal data angles than others. The major stories of the unprecedented year that was 2020 featured data angles that weren’t just pivotal, they were essential. It’s not hyperbole to say that our lives depended on this data, and on those who attempted to communicate it to us.

If you think about it, there has likely never been a time when more humans around the world watched numbers about a single topic update on a continual basis for such a prolonged period of time. The COVID-19 confirmed case count and, tragically, the death count have occupied our collective consciousness like no other data set in the history of our species. And then there was the United States presidential election in November of last year, during which time billions of eyes around the world watched updated vote counts roll in by the minute.

Given these examples, and so many others such as global warming, it’s safe to say that data journalism has never been more critical.

There’s a problem, though, and it’s a big one: many of us simply don’t grasp the data angle of these critical stories very well. Data literacy is defined by Javier Calzada Prado and Miguel Ángel Marzal as “the component of information literacy that enables individuals to access, interpret, critically assess, manage, handle and ethically use data.”

Collectively speaking, our level of data literacy just isn’t where it needs to be, and the gap that exists in our knowledge and skills can lead to dangerous misunderstandings about our environment.

For example, talented data journalists all over the world such as John Burn-Murdoch of the Financial Times worked fervently for more than a year to share COVID-19 data with us. Their efforts kept us informed about a pandemic that affected daily life in so many ways. We owe them a great deal of gratitude for the many long nights they spent (and continue to spend!) pouring over the data and triple-checking their calculations.

And everyday readers aren’t the only ones paying attention. The data and charts on COVID-19 published by the team at Our World in Data have been used by public health agencies of governments around the world to make decisions that have saved countless lives.

If we look carefully, though, we notice an interesting detail. Sometimes news sites like FT and non-profits like Our World in Data shared COVID-19 data in the form of line charts that feature logarithmic scales, a perfectly suitable way to show the growth rate of a virus that can spread exponentially. Other times they shared the exact same data using line charts with linear scales which result in lines that curve dramatically upward rather than forming the straight lines of the same series plotted against a log scale.

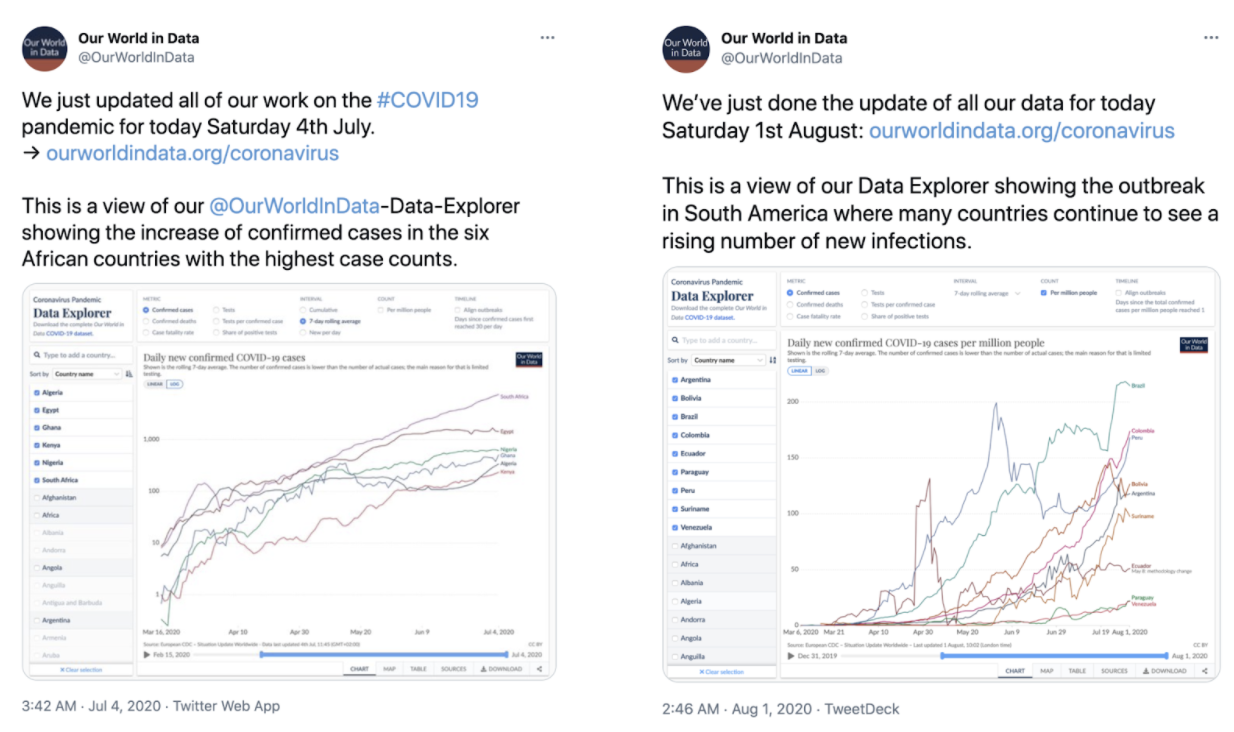

Fig 1. Two tweets by @OurWorldinData showing images of COVID-19 data using a logarithmic scale (left panel, 04 July 2020) and a linear scale (right panel, 01 Aug 2020).

How does this seemingly technical decision about how a chart is formed affect cognition and attitudes? It’s hard to know for sure, but forthcoming findings by researchers at Yale Law School and London School of Economics & Political Science about the way people interpret charts with logarithmic scales seems to show what we might expect: that many people still struggle to answer basic questions using log scales.

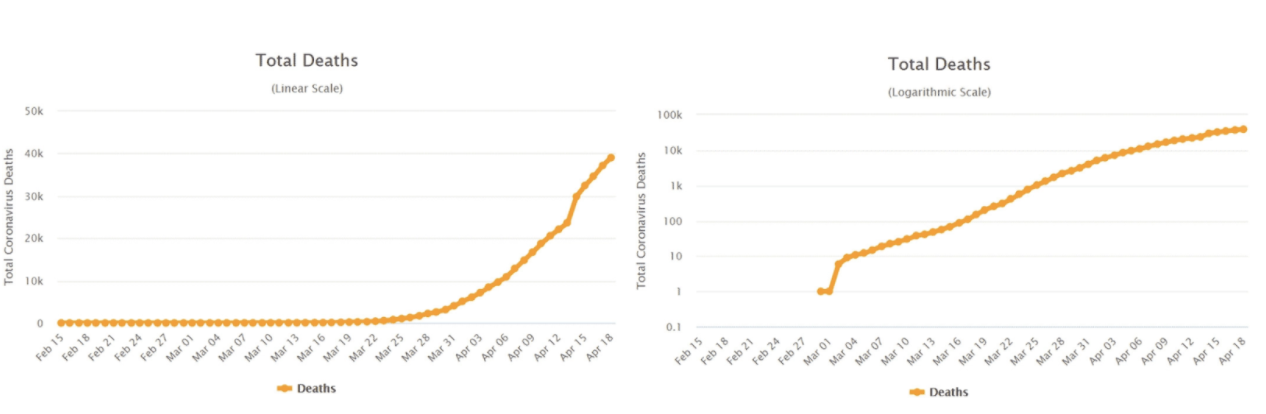

In the study, a double‐blind experiment involving 2,000 U.S.-based participants, respondents who were shown logarithmic charts had a harder time accurately answering questions such as whether the number of deaths increased more during one week or during the following week. According to the study, about 3 in 5 participants incorrectly answered the question when shown the logarithmic scale on the right of the following figure.

Fig 2. COVID‐19 related deaths in United States between February 15th and April 18th in a linear scale (left panel) and in a log scale (right panel). Source: www.worldometers.info

And it isn’t just that they often arrived at an incorrect answer when using a log scale. According to the study, readers’ misinterpretation of the charts led them to make inaccurate predictions, and their attitudes about the relative risks were affected as well.

Unfortunately, switching to the linear scale didn’t seem to completely inoculate readers against the mental disease of misinterpretation: almost 1 in 5 participants who were shown the linear scale line charts also answered the exact same question inaccurately. Are there other questions that weren’t asked in the study for which log scales would produce more accurate answers that linear scales? Perhaps.

All of this underscores an undeniable fact: that we’re far from perfect when it comes to making sense of visual encodings of data, even when the topic is a matter of life and death.

So where do we go from here? How can we cope with this reality and attempt to close the greatest education gap of our era?

Well, publishers like Financial Times and Our World in Data have taken upon themselves the roles of teacher and trainer, with detailed and helpful primers on how to read their charts included in their articles and on their tracker pages. They also engage in explanatory threads on social media and even produce informative videos to explain their decisions and the impact these decisions might have on the reader.

Furthermore, the graphics they provide aren’t static but rather interactive, like the one below that allows the reader to toggle between linear and logarithmic scales. These elements at least give the careful reader a chance to arrive at an accurate understanding of the situation.

Of course we’ve only discussed the impact on readers’ cognition of one single design choice: linear vs logarithmic scale line charts. If you look again at Figure 1 above, you’ll notice another difference. One shows confirmed COVID-19 cases and the other shows confirmed COVID-19 cases per million people – a normalised figure that puts all countries on a similar playing field by dividing their case counts by their population.

There are many more such choices. Journalists can show cumulative counts that continue to climb or they can show daily counts that might rise or fall. For daily counts, they can show raw figures or they can show a rolling average that smooths out spikes that are likely just an artifact of the reporting procedure. And they can choose to show different country outbreaks when they happen in time or they can align them to aid comparison.

All of these decisions, and so many others, are what makes working with data so challenging and so interesting. There are multiple data angles to each story, and each data angle gives a different perspective about what’s happening. Choosing the data angles to incorporate into the story is like trying to solve a multi-dimensional puzzle. Tantalisingly, these puzzles are collaborative ones involving both journalists as well as their readers at large.

Unfortunately, neither group is perfectly fluent in the language of data, and the level of variation in fluency in both groups is large. For this reason, the exchange can be messy, and the puzzle only partially solved. In this respect, communicating data is like other forms of human communication: highly imperfect and subject to errors in translation.

Attempting to solve these communication puzzles one by one, or at least making choices that improve our chances of solving them, is what data journalism is all about.

If my time guiding the Tableau Public platform taught me anything, it’s that working with data sets that relate directly to our communities, our world, and our lives can build our fluency in the language of data. Running Data Literacy at DataLiteracy.com has cemented this teaching philosophy for me – all of our training courses involve open, public data sets. I want my trainees to have a similar experience as the reader who encounters great data journalism: they don’t pay attention to the fact that they’re learning about a chart type or a statistical concept or method. They just pay attention to the fact that the data is showing them something fascinating about the world. And so they accomplish the former without really knowing it.

This, to me, conveys the potential that data journalism has to help us close the Great Data Literacy Gap. It’s why the state of data literacy on this planet is depending on data journalists to continue nudging us forward, one “data angle” at a time, even if we do struggle to get it right.

The importance of data journalism to data literacy - Ben Jones - Live chat on Discord at 4pm CEST (10 June 2021)

9 min Click to comment